Ghaffar-Kucher Studies the Religification of Pakistani-American Youth After 9/11

August 31, 2011 - For Muslim Americans, 9/11 delivered two blows: the tragedy of the attack itself and the climate of prejudice that followed.

The cost to one particular group – Pakistani-American youth – became particularly clear to Ameena Ghaffar-Kucher as she was conducting an ethnographic study in a public high school located in one of New York City's ethnically diverse outer boroughs.

“I did not start out to explore ‘how it feels to be a problem,’” says Ghaffar-Kucher, a lecturer at Penn GSE and associate director of its International Educational Development Program. In fact, she explains, “September 11 wasn’t even on my agenda. I just wanted to understand the experiences of these Pakistani kids.”

“I did not start out to explore ‘how it feels to be a problem,’” says Ghaffar-Kucher, a lecturer at Penn GSE and associate director of its International Educational Development Program. In fact, she explains, “September 11 wasn’t even on my agenda. I just wanted to understand the experiences of these Pakistani kids.”

The school where Ghaffar-Kucher conducted her study has a diverse student body – kids with roots in Italy, Russia, Poland, China, and any number of Spanish-speaking countries – and a history of educating the children of immigrants. The Pakistani students predominate in the school’s sizable Muslim population, but others hail from Palestine, Bangladesh, Yemen, and India.

As a Pakistani Muslim herself, Ghaffar-Kucher wanted to counter the prevailing notion of Muslims as a single, homogenous group by focusing on a particular subset: working-class and lower-middle-class Pakistani-American youth.

In particular, she wanted to learn more about how these young people manage the expectations facing them – from their families and their community and also from their teachers and their school. “My assumption was that they would be different – but not necessarily dichotomous – expectations, and I was curious about how these kids would succeed in navigating them.”

But everywhere she went, 9/11 loomed large. Students described their school life before, when no one much cared about their religion, and after, when their religion was all that anyone seemed able to see. In a recent issue of American Educational Research Journal, she explains the phenomenon, illustrated by one 14-year-old boy who told her, “Like, before there was just, like, regular people, you’re from Pakistan…. They don’t think of it as a good thing or a bad thing.”

After 9/11, though, everything changed: in the words of Yasir, also 14, “It really did [change] because of my religion and where I come from. The kids in my classroom used to call me ‘terrorist.’”

The more Ghaffar-Kucher engaged with the students – her study included participant observation sessions, one-on-one interviews, focus groups, and home visits – the more clearly she saw the bind they had been caught in.

Of little consequence before 9/11, their religion had come to define them. Shunned because they were Muslim, they increasingly identified themselves as such, transforming the negative experience of ostracism into the positive of solidarity and, in a vicious circle, setting themselves further apart from their non-Muslim classmates. Ghaffar-Kucher refers to this as religification.

In the school itself, their uneasy situation was exemplified in the “Urdu class.” Unlike the many heritage-language classes the school offered to its multi-ethnic student body, this class wasn’t a language class – the school couldn’t find a certified Urdu teacher – but rather a “citizen orientation program” to acquaint students “with the culture and expectations for citizens in the U.S.”

As a de facto requirement for the Pakistani-American kids, the class delivered a paradoxical message: “It touted citizenship,” Ghaffar-Kucher explains, “as well as inclusiveness through the validation of students’ backgrounds and languages, but in reality it served to segregate the students.”

Stranded by post-9/11 politics – both local and global – the students could find no way to reconcile their Muslim and American selves. “The youth felt that an American identity was no longer an option…” Ghaffar-Kucher writes, “a realization that increased their desire to find other ways to belong, such as elevation of their Muslim identity, playing into the terrorist stereotype, and in a sense, rejecting their American citizenship.”

For her next study, Ghaffar-Kucher would like to see what happens to the same cohort once they hit college and as they get further and further away from 9/11. “My sense is that college is a different kind of space; that it might offer forms of social and cultural capital that perhaps allows youth to feel they can be both Muslim and American.”

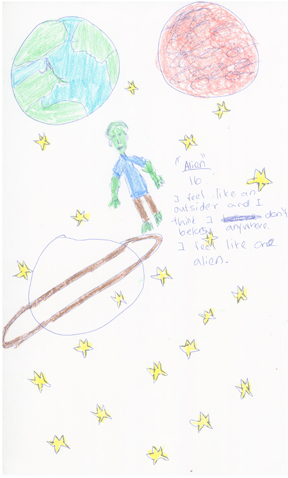

Photo Caption: A 16-year-old Pakistani-American student who participated in Ameena Ghaffar-Kucher’s study made this drawing to illustrate how he saw his relationship to Pakistan and America. His caption reads, “Alien, 16, I feel like an outsider and I think I don’t belong anymore. I feel like an alien.”