Who Are These Guys?

September 10, 2008 - It all depends on who you ask.

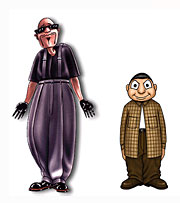

Pelon (the tall guy with the glasses) and Cricket are two of the “Homies” created by LA artist David Gonzales, based on characters that he observed in his neighborhood. Homies represent social types typically found in places with a longstanding Latino presence, and each comes with a life story. Pelon, for instance, is “basically a hustler,” Gonzales explains “…always selling hot merchandise.” But Cricket is more nerd than gangster.

In their LA birthplace, Homies sparked a time-worn debate about racial stereotyping and the gangster lifestyle, with the LAPD attempting to ban their sale in 1999. But Homies have found an eager market among young Spanish-speakers in communities that have only recently seen an influx of immigrants, and kids growing up in these communities are putting their own spin on the meaning of these characters in their lives.

In their LA birthplace, Homies sparked a time-worn debate about racial stereotyping and the gangster lifestyle, with the LAPD attempting to ban their sale in 1999. But Homies have found an eager market among young Spanish-speakers in communities that have only recently seen an influx of immigrants, and kids growing up in these communities are putting their own spin on the meaning of these characters in their lives.

Over the past few years, Penn Professor Stanton Wortham has been studying one of those communities, with a particular eye on how its youth deal with complicated issues of identity development. New Marshall (pseudonym) — a town of 30,000 located near a large city in the Northeast — has seen a dramatic growth in its Latino population, rising from 2.7 percent in 1990 to 10.5 percent in 2000.

In New Marshall, some people do indeed equate Homies with gangsters, reflecting their fear of gang activity. But New Marshall is not LA, and responses to Homies — and to the Mexican-American world they reflect — is surprisingly complex.

In the schools, teachers who are concerned about misbehaving teens may interpret Homies as signs that some Mexican students are becoming like resistant urban youth. But in other contexts — even in supportive classrooms — students can construe these figures in a variety of ways.

While most of the Mexican youth also see Homies as gangsters, only a few identify with them as such. Rather, the majority identifies with them as Latino models not often found in American mass media. But even that response is not monolithic, since many young people drew a distinction between newly arrived Mexican immigrants and Chicanos, that is, native-born Americans of Mexican ancestry.

The wide variation in the ways Mexican youth in New Marshall interpreted the models offered by Homies shows a plasticity that might not be possible in places like Los Angeles, where certain roles like "Chicano" and "gangster" are more fixed. Because the Mexican immigrants of New Marshall encounter Homies in a relatively new and open environment in terms of Latino identity, they can generate a greater diversity of meanings as they come into contact with mass-mediated models of personhood.

Even more significant, though, is the more fluid context that characterizes a place like New Marshall. In LA, where Latino identity has become more fixed over the decades, Homies are more often construed as gangsters.

But in New Marshall, where the identities have not yet hardened into stereotypes, Mexican immigrant youth are free to experiment — at least among themselves and with sympathetic adults — trying out different models of personhood and affiliating with and against the Homies as they do so.