Mother Scholar Janay Garrett blends activism, research, and motherhood

Janay Garrett, center, with her husband James and their daughter.

Dean Janay Garrett is working from her new home office in the spring of 2021. In January, the Stockton, California, native left Philadelphia for West Haven, Connecticut, a place where her two young children were enjoying adjusting to having a backyard to play in. While she works, her daughter comes to the door, asking for “just one hug” in the middle of a call. It is the sort of interruption that has become commonplace for working parents thrust into home office and virtual schooling arrangements by the COVID-19 pandemic, but for Garrett, it is utterly normal – it is a part of motherwork. And that is something this doctoral student in Penn GSE's Interdisciplinary Studies in Human Development program cares deeply about.

An introduction to activism

In her mid-20s, Garrett decided she wanted to go to graduate school. A Google search for “education, race, gender,” led her to discover the Social and Cultural Analysis of Education program at Cal State Long Beach. It was 2014, and as Garrett watched early actions at the start of the Black Lives Matter movement unfolding in Los Angeles, she was galvanized to get involved. Friends at UC Berkeley invited her along to her first direct action while she was home on break. She took part in a protest in Oakland, holding healing space for a shutdown of the BART transit system. She was struck by the power of the moment, and how different her perceptions of activism had been from media portrayals in contrast to what she was experiencing on the ground.

When school resumed, she joined the BLM Long Beach chapter. She dug in to her master’s program, reading and attending events and presenting at conferences all over Southern California. “All these ideas – in Black feminism, in critical race theory, in Indigenous and queer activism – just cracked my mind and heart open,” she said. Simultaneously, she was trained as a restorative justice practitioner, ultimately serving at a school site for youth–largely Black and Brown–who had been pushed out of the mainstream school system. And where she thought going into the work she would be taking on an intensive restorative justice intervention, “it ended up being much more like just showing them someone cared and really truly believed in them.”

Through all of this, she developed a strong foundation in context, but felt like there was something missing. How did human development–someone’s individual life course–influence who they become, and vice versa? “How can something happen to me when I’m three or four or five, and suddenly, when I’m 25, it shows up?” It was beginning to answer this question Garrett knew she wanted to pursue further.

An inspirational mother-scholar-activist

At the same time she was in school, she began meeting influential leaders in the BLM movement who would shape her own trajectory, including Dr. Melina Abdullah, at Cal State Los Angeles. Garrett speaks with reverence for Abdullah, whom she witnessed not only in her activism, but simultaneously as a mother. “How do you raise such critically conscious children?” Garrett asked, and as Abdullah welcomed her in to observe how she connected organizing and motherhood, Garrett not only wanted to file away these ideas for her own future parenting, but had found a research theme she wanted to pursue. She wrote her master’s thesis on how Black women activists raise critically conscious children.

In 2016, after a conversation with Dr. Howard Stevenson and several friends in doctoral programs at Penn GSE, Garrett enrolled in the Interdisciplinary Studies in Human Development Ph.D. program. Her then-partner, now husband James J. Garrett I enrolled in the master’s program in Reading/Writing/Literacy the following spring. And together, they built their home and scholarly community among faculty mentors and fellow students in Philadelphia.

Adjusting to the hidden curriculum of doctoral work

Early on in the doctoral process, Garrett encountered the hidden curriculum – all the unspoken codes of behavior between graduate students and faculty. While she came in with a strong point of view from her master’s thesis, it took some adjusting to understand how she fit into the role of a mentee, what dispositions she needed to adapt to work with her mentors, but ultimately, how she would transition from student to a researcher in her own right.

In meetings with her adviser, Dr. Stevenson would probe her thinking, asking her to consider pieces she hadn’t thought of, pushing her to go deeper in her questioning. Sometimes, frustrated at a lack of cohesion, she’d express her anxiety about the work, about her developing ideas.

“Let it bake,” Stevenson would tell her.

And so Garrett let the ideas bake. She began working for the Racial Empowerment Collaborative, a research center under Stevenson’s direction, where she mentored master’s students, led presentations, and aided in the center’s communications work.

Motherwork and scholarship come together

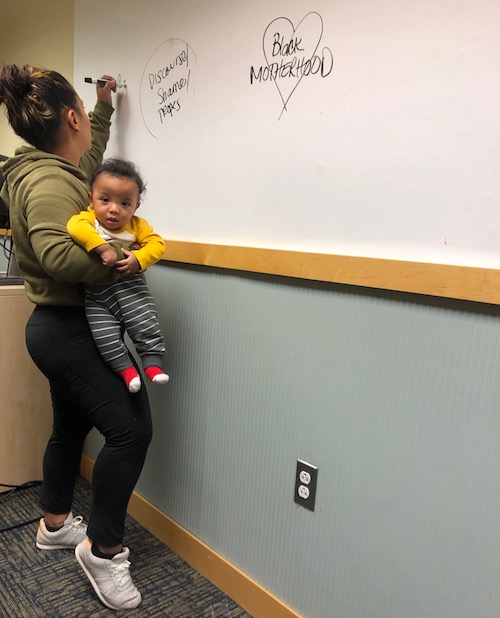

She kept at her studies while becoming a mother, asking for grace from faculty and peers as she went from pregnancy to bringing her young child with her to campus. “Especially when I was super-pregnant,” she says, Jasma Lee, Penn GSE’s much-beloved front desk guard, was a key part of her support structure. She continued with her studies, kept meeting with Dr. Stevenson, and kept honing her ideas. She was becoming a researcher, becoming a mother, and becoming both at once.

Current events never stopped shaping Garrett’s scholarly lens. Just as she was preparing to take her comprehensive exams, federal policy shifts led to increased family separations at the US-Mexico border. She thought about the developmental effects on children and mothers. As this massive humanitarian crisis continued, Garrett turned to literature on Chicana motherhood, reading the Chicana Motherwork Anthology. And not only was she reading about it, she herself was experiencing motherhood at the same time, with her daughter, a toddler, and pregnant with her second child. As her daughter slept, late at night, Garrett sat up writing at the kitchen table. The ideas streamed out of her, along with a flood of emotions. She checked in with Stevenson, who assured her this passion meant she was going in the right direction.

What was happening to these children and mothers was traumatic. But, Garrett says, it went far deeper. “This child is an extension of my soul,” she says, “and so how could you possibly rip this child away from me?” Turning to the literature, she began asking more questions. What is motherhood? What about other mothers, like aunts? She wrote and wrote. And when she was finished, with feedback from Stevenson and Dr. Sharon Wolf in hand, she had to figure out what to write about next.

Finding her voice in the scholarship

Garrett turned to the concept of matrescence – the process of becoming a mother – a concept from anthropology centering around the biological, psychosocial, political and spiritual changes people experience during the transition into motherhood. But, she found, most of the literature was about white women, or when it discussed women of color, it was from a deficit lens. What about community? About intergenerational care and labor? About motherwork itself?

And with that, she had two frameworks–motherwork and matrescence–that would shape her next set of questions. On top of that, she had noticed her own self-talk, both as a graduate student and as a parent. She noticed her own anxiousness, as a Black and Chicana mother protecting her children.

What if, she thought, she could center the voices of Black mothers, documenting their self-talk as an intervention in and of itself? And then, how could that self-talk, the acknowledgement that they are thinking about the wellness of themselves and their children all day, be something that could be used to communicate with partners, with teachers, with doctors? It began to seem like those ideas that she’d been told to let bake were ready.

“I’ve heard teachers say ‘Parents in Philadelphia don’t care about their kids,’” Garrett says, noting the damage a statement like that does in and of itself. “But if you stop and think about all the decisions this person had to make, from their doorway to the bus stop, you would have a totally different lens on how you’re thinking about parent engagement and parent support.”

So in 2020, while the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted and upended may things, another round of applications for funding and fellowships opened up, too, and this time Garrett had a clearer focus to her research topic. Garrett was named an American Association for Hispanics in Higher Education (AAHHE) 2021 Graduate Fellow, received a graduate fellowship from the Center for the Study of Race, Ethnicity and Education (CRSEI), and was awarded the Penn Graduate and Professional Students Association (GAPSA) Provost Fellowship for Interdisciplinary Innovation (2021). Her dissertation work is guided not only by her adviser, Dr. Stevenson, but with the support of Dr. Sharon Wolf, Postdoctoral Fellow Dr. Nkemka Anyiwo, Dr. Imani Perry at Princeton, Dr. Marsha Richardson, and with an extra shout-out to Dr. Wendy Chan for, she says, making stats relatable to her.

A new opportunity presents itself

In the fall of 2020, Garrett taught a class, Social Justice in Developmental Psychology: Applied Frameworks for Critical Research and one of her students, Katrina Garry, a student in Penn GSE’s Higher Education M.S.Ed. program, came to her with a confession mid-semester.

“I found your CV online,” Garry told Garrett during virtual office hours, “and I’ve passed it on to my colleagues. There’s this opening here at Yale, and I think you’d be perfect for this job,” she said. The job? Assistant Dean of Student Affairs, working in the Office of Gender & Campus Culture and the Alcohol and Other Drugs Harm Reduction Initiative at Yale University. Garrett jumped at the chance, remembering a time long ago, as an undergrad, where she had joked with a beloved dean that she would come for his job someday.

In her new role at Yale, Garrett is working with a few key staff members, but also with a large group of undergraduates. Her office works to build a healthy campus culture, broadly speaking, and does work including sexual violence prevention and building healthy relationships. “A healthy campus culture does not come from punitive measures and approaches–that’s proven not to work,” she says.

All of Garrett’s own experiences, from thinking about the effect of developmental experiences in childhood that may manifest in someone’s 20s, or her intersectional approaches to research, or her work in restorative justice with adolescents in California on violence prevention, is ready for this new stage in her professional trajectory. She is putting her research and experience into practice on the job, attributing the fact that she as a psychologist inhabiting this job is itself evidence of the work of students pushing for change within universities.

“When I interviewed, I was true to myself. I want to be not just representationally important in this role, in the multiple identities I hold, but also for students to know they have an ear with someone like me within this institution,” she says. “These students will become the leaders of the world, for better or worse, and there’s an opportunity to make an impact and support the students who’ve been organizing on campus already.”

<> <> <>

Garrett expects to complete her dissertation in 2022, with research on motherwork and matrescence that will contribute a critically neglected perspective to the field. As university campuses return to more in-person operations, Dean Garrett’s office will be key in shaping campus culture after a period of such upheaval. And at home, Garrett’s family will welcome a new child into the world. It is a blend of research, activism, and motherhood she once admired in a mentor she herself is now putting into practice.