Faculty Expert

-

Sigal Ben-Porath

MRMJJ Presidential Professor

Policy, Organizations, Leadership, and Systems Division

Teachers logging into their virtual classrooms this week have a choice: Address the protests happening across the country, or try to move along with year end lessons.

Sigal Ben-Porath, a Penn GSE expert in civic education and a former high school teacher who worked in conflict areas, asks teachers not to pretend protests about institutional racism and police brutality don’t exist.

Students, especially older students, will remember this moment and how they felt. Ben-Porath says the most educative action teachers could take would be to have the hard conversation about what is happening in the United States right now.

This is true for students of any age, and especially true for students who are living in the communities at the center of protests.

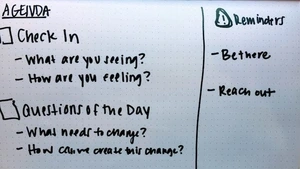

Ben-Porath suggests teachers start with a check-in, and then ask two questions.

The check-in

Since students are logging in virtually, teachers can begin the conversation with basic questions:

What are you seeing around you? What does your block look like? If the students are older, a teacher can ask if any of them joined in a demonstration, and if so, what they saw.

Ask students what they have heard about the protests, and where they heard it from. If there are obvious factual errors, teachers should correct them, but this is about laying a foundation for the conversation. Let students talk with emotion. Let them talk about their pain, their anger, and their fears.

Some students may not be comfortable sharing emotions or talking about their participation in protests in a class-wide video conference. Teachers can reach out or have open office hours where students can share their thoughts and experiences in a smaller setting. If students aren’t logging in, and we know many schools saw drops in attendance for virtual sessions, this is a good time for teachers to try and engage again.

Question 1: What needs to change?

This is the basic question of political action and civic engagement, and it’s the basic question of protest.

Even in elementary school, students have an understanding of our shared community. They have a sense of their neighborhood and neighborhood institutions. What within this shared or common environment needs to be better?

Through this lens, teachers can talk about the protests and the anger behind them as an attempt to affect change. This is a way for students think about ideas of justice, about what they value, and about what they see in the world, how they feel about what they see, and what they would like to see.

Question 2: How can we create this change?

The world can look bleak right now. People are rightfully angry about the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and Tony McDade—and that is merely the names of those killed in the last few weeks. At the root of the protests is America’s centuries-long history of institutional racism.

To create conditions for civic action, you need a shared goal, and you need a sense of hope.

So how do we—as individuals, as members of a family, as a class, as civic actors—create the changes we are looking to see?

Public disruptions are one way to create change. They played a key role in the Civil Rights movement, the women’s suffrage movement, and the push to change the country’s policy on AIDS in the 1980s, among others. In Philadelphia, a teenage protest in 1967 was the start of a movement that eventually resulted in African American history becoming required curriculum in the city’s public schools.

It’s crucial that teachers are honest: Some protests have advanced social justice, but the progress has not been consistent, or without setbacks.

As students think about how they can create the change they want to see, emphasize that protests are only one tool of civic engagement.

Artistic expression, graffiti, dance, public education, petition drives, and voting all have their places too. Above all, every significant and lasting advance happened because people from different groups were able to form coalitions, negotiate, and work together.

Subscribe to the Educator's Playbook

Get the latest release of the Educator's Playbook delivered straight to your inbox.

Media Inquiries

Penn GSE Communications is here to help reporters connect with the education experts they need.