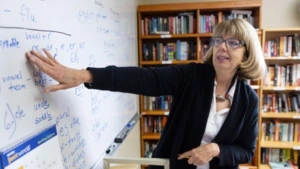

Photo credit: Stina Booth

Jeanne Smith goes behind bars every day for the Vermont Department of Corrections to teach reading to incarcerated people. It is the latest step on a long career path that the literacy specialist first embarked upon 40 years ago when, as an undergrad, she joined a work-study program teaching adult literacy in Philadelphia community centers.

“I was stunned when I started that job,” she said. “These folks could not read—a basic skill most of us take for granted. They were there because they wanted to learn. It made me want to become an educator.”

Graduating with a degree in psychology, Smith continued working with the adult literacy program as an AmeriCorps volunteer. But she was self-taught, researching her own reading materials and trying different methods to improve her skills and help her students. Seeking more formal training, she applied to Penn GSE.

“I didn’t know much about education, so I was really soaking it up,” she said of her time at Penn GSE. “All my professors were great, and I really loved being in the Penn community.”

Smith received her master’s degree in reading and language arts, and then worked for several years as a literacy education director in Philadelphia.

Twelve years ago, she applied for a teaching position with the Vermont Department of Corrections. And though she had taught reading to scores of children and adults in classrooms, after-school programs, reading clinics, and community centers, she admitted she was initially intimidated by her newest students.

“I had to remember that these were people who . . . made mistakes and were trying to get their lives back,” she said.

Smith quickly became the go-to teacher for those who needed the most literacy support, many of whom came from backgrounds scarred by domestic violence and sexual abuse.

“Those were really the ones I was most concerned about,” she said. “I knew they were going to continue to have the worst time trying to get anywhere in life without support, help, and education.”

Four years into the job, Smith was asked to create a system-wide literacy program, transforming what was once a hodgepodge of teaching methods into a science-based, step-by-step adult education program. The program is required for inmates 23 years old and younger but is open to all who could benefit from it.

“After we developed a curriculum for the adult basic education (ABE) skill level, we were able to clearly state what was needed for a solid program,” she said.

It has taken time, and progress has come in fits and starts, but the Vermont correctional education program is now firmly established and includes not just ABE, but also a GED program, a high school diploma program, and a workforce education program. Currently, there are 20 students enrolled in reading and writing and 44 in study skills. Smith herself teaches six students and has two new referrals.

“It will grow,” she said. “The referral process, classes, assessments protocols, syllabi, and training have taken a good, long time to put in place. We now have staff trained in basic skills in all six facilities [across the state].”

There are already a few success stories. One of Smith’s students, Joe, had a high school diploma but was reading below the sixth-grade level. He wanted to get a commercial driver’s license (CDL) but had trouble understanding some of the words in the state’s CDL manual. Smith used the manual to teach him decoding skills. That kind of innovation and flexibility is crucial when teaching literacy to adults.

“You have to do more in-depth teaching of language structures,” she said. “You have to also bring in more multisensory approaches to processing language, such as magnet tiles that students move around. It gives the brain more to grasp onto to process how the language works.”

Smith is building a library of topics of interest and specific book titles for younger students. But, one thing she needs even more than books, she said, is more research on teaching adult literacy, especially for those behind bars.

“I would like . . . to really have more scholars of education do research in adult literacy, including [for] people in prison,” she said. “There isn’t enough to guide us.”

This story first appeared in the fall/winter 2024 issue of Penn GSE Magazine.

Media Inquiries

Penn GSE Communications is here to help reporters connect with the education experts they need.