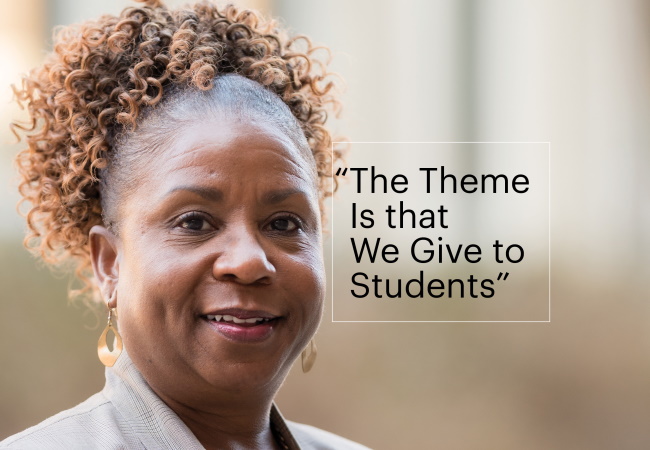

In her role as professor of practice at Penn GSE, Dr. Andrea Kane brings the perspective of twenty-five years’ experience in K–12 public schools to her work with aspiring and current teachers and leaders. Photo by Ginger Fox Photography

interview by Juliana Rosati

As schools across the nation grapple with issues of race, social justice, curriculum, health, and staffing, Dr. Andrea M. Kane brings the perspective of twenty-five years in Maryland and Virginia K–12 public schools to her work with aspiring and current teachers and leaders at Penn GSE. A professor of practice who joined the School in 2021, Kane works with students in the Mid-Career Doctoral Program in Educational Leadership and the Teaching, Learning, and Leadership master’s program, preparing them to address complex issues and provide valuable learning opportunities to all students.

In roles from teacher to administrator—most recently, superintendent—Kane gained recognition including the Governor’s Citation for instructional leadership, the first National Blue Ribbon School in Queen Anne’s County Public Schools’ history, the State of Maryland’s highest graduation rate for four consecutive years, and a ranking of six out of twenty-four school districts in Maryland. As the first African American superintendent of Queen Anne’s County, Kane set professional and personal goals focused on implementing equitable practices across all areas of the organization. We sat down with Kane to discuss her teaching, her practice, and her transition to Penn GSE.

At Penn GSE, you teach courses about educational leadership. What are you aiming to impart to your students?

I always want to differentiate my instruction to make it meaningful to students with a variety of professional backgrounds and goals. Some of the areas we cover in my courses are instruction, policy, school improvement, professional development, and self-care. Throughout, we apply theory to practice using an equity lens. We’re building educators and leaders who can employ equitable practices across a classroom, a school building, or an entire district.

I want our Teaching, Learning, and Leadership master’s students to know that I can relate to their challenges as prospective or current teachers. Sometimes they’re intimidated—they say, you were a superintendent and I haven’t even taught yet, should I even be in this class? And I say, absolutely you should.

Most of our students in the Mid-Career Doctoral Program in Educational Leadership are working in schools every day, facing a variety of challenges. Having worked in urban, suburban, and rural districts helps me to be able to brainstorm approaches with them. We want to provide a forum that supports them in their everyday leadership as well as in their visionary leadership—their aspirations for the future.

Instructional leadership, equity, and the connection between the two have been themes of your work. How have you approached these areas?

Overall, I’ve looked at who is learning and who is not, and what instructional practices we can employ to ensure that children who are at the margins are brought to the center and made a focus of instruction, while we continue to challenge all of the students. The focus isn’t just one group of students—it’s got to be everybody.

Equity looks different in different places, but the theme is that we give to students—we ensure they have what they need to meet their full potential. In Anne Arundel County, Maryland, I was part of a team that started a district-wide initiative to narrow or eliminate achievement gaps. We used the Data Wise Improvement Process from Harvard, looking at students’ results to identify areas where teachers needed to make adjustments in their instruction. We would consider the classroom environment, the instructional materials, and the delivery of instruction to understand how to improve in areas where students were struggling. I brought the same approach to Richmond, Virginia, and Queen Anne’s County, Maryland.

What is an example of an area in which you sought improvement?

When I looked at the data in Queen Anne’s, I saw that the majority of the students were white, and also that there were hardly any students of color in Advanced Placement classes. Research tells us that students who enroll in rigorous coursework in high school fare better in college, and we wanted to open the doors to college preparation. We worked with an outside agency and implemented strategies that increased the enrollment of nontraditional students—Black, Brown, and poor—in Advanced Placement classes. We matched students with potential to caring teachers who mentored them. We reconsidered the prerequisites for enrollment and the instructional strategies. In addition, we diversified our materials of instruction to send a more inclusive message to students.

Beyond instruction and access, what are some other areas you have addressed to make schools more supportive of all students?

As a district-level leader, I’ve made sure to find out what students think about the school environment. If schools take a thoughtful approach to asking students their opinions, they’re going to hear the truth of the matter. I’ve worked to diversify teaching staff, often going out myself to recruit teachers of color from historically Black colleges and universities so that our students could see themselves reflected in the adults at their school. I’ve also required professional development in culturally relevant instruction, cultural proficiency, and bias and antibias-related behaviors for every employee, from bus drivers to administrators, so that we could understand and begin to value cultural differences and how we might make various groups of students feel welcome. In addition, I’ve addressed the ways in which inclusion can be about ability, rather than culture—engaging students who receive special education services and addressing them appropriately makes a difference.

You are a member of the advisory board for the Achieving Academic Equity and Excellence for Black Boys Task Force with the Maryland State Department of Education. What does that work involve?

We kept seeing data that shows Black boys are behind everybody else in school, and we wanted to do something about it. I was on a team convened by Dr. Vermelle Greene, a member of the Maryland State Board of Education. We conducted research and presented a proposal with recommendations for social and emotional behavioral supports, recruiting and training teachers and administrators, and curricula and instruction that the Maryland State Department of Education approved. Now we have pilot schools implementing a variety of strategies and programs to address areas such as academic performance, behavior, and sense of belonging. The approach is to recognize and build on Black male students’ assets in order to improve their outcomes.

[[image|left|caption=A former school superintendent, Dr. Kane differentiates her instruction to make it meaningful to students with a variety of professional backgrounds and goals. Photo by Ginger Fox Photography|alt=Dr. Andrea Kane is seen wearing a mask and speaking to a student sitting opposite to her in an office.|width=400|src=/sites/default/files/penngse_kane_student_office.jpg]]

Teaching about race in schools has become a controversial issue as some communities have sought to restrict curriculum content, including in Queen Anne’s County. How would you describe the approach that you would want schools to take?

We need to teach children the truth about our history. Let’s talk about why slavery happened, and let children reflect on the conditions that allowed it to happen, and how important it is for those not to find their way into the current reality. Children understand that it was wrong. This is not about making white children feel ashamed because white people were slave owners, any more than it’s about making Black children feel ashamed because their ancestors were enslaved. This is about helping children grapple with hard issues, so that they grow up to be adults who can do the same.

Your commitment to environmental education led to Green School certification in 100 percent of Queen Anne’s County schools and a $1 million grant for a summer program. Have you continued to pursue work in this vein?

Yes, environmental education is my second love! Equity is first, and I’ve been able to fuse the two. I sit on the board of directors of the Maryland Association of Environmental Outdoor Education (MAEOE), and recently we’ve focused on diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice. We want to help students not only become good stewards of the environment, but also understand why environmental conditions are different in different parts of the state. Because climate change and some environmental issues disproportionately impact impoverished communities (and more often than not, those who are Black, Indigenous, and people of color), MAEOE acknowledges the importance of dismantling systems of oppression and injustice that prevent equitable access to nature. Overall, we want to show that this work is about making the environment better for everybody.

What has it been like to move into your role at Penn GSE?

My transition has been fabulous. I can truly say that every person I have met has been welcoming. I appreciate the freedom and openness that allow me to teach what I want to teach and to have conversations with my students to ensure the content is meeting their needs. At Penn GSE, there’s a wonderful willingness to keep improving our practices to best support our students.

This article appeared in the Spring 2022 issue of The Penn GSE Magazine.