For more than a century, Penn GSE has developed teachers who are driven not just to prepare their students for success, but to transform and advance education itself. Today, Penn GSE programs are helping to evolve and support preK–12 education by offering a mix of the theoretical and practical, combined with a critical focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI).

Here, four alumni—a mathematics education scholar and practitioner, an English-learners teacher, a STEM education professor, and a school-based teacher leader—share what motivates them to stay in the game at a time of recruitment and retention hurdles. They also discuss the ways they are creating more equitable learning opportunities for all students.

CREATING CULTURALLY RELEVANT CONTEXT

Natasha Murray, GRD’05

Natasha Murray likes to throw a curveball to teachers. As a district administrator in the New York State Education Department, she facilitates workshops for math and science Master Teachers, and she often incorporates a fifth-grade-level math problem that involves the sport of cricket.

She finds that most of the American-born educators are stumped, unable to solve the simple problem given their unfamiliarity with the bat-and-ball game with English roots. The exercise, she says, nicely illustrates her point: context matters.

“For students to really solidify concepts they’ve learned, they need to build upon existing knowledge,” says Murray, the coordinator of math and data at a large, suburban, public school district and an adjunct professor at the State University of New York College at Old Westbury on Long Island.

Often, curricula fail to take context into account, she says. One state assessment used a football scenario to test student knowledge of parabolas, Murray says, not accounting for those from immigrant families who might associate “football” with soccer and become confused.

“Through these workshops,” she says, “the participants redesigned the math curriculum for their schools, and we ensured diversity and representation within the curriculum. That impacted thousands of students across the state.”

Murray has a longstanding commitment to creating opportunities for young people from historically marginalized groups. Early on, she noticed the disparities in education, first among fellow college students, where family wealth seemed to determine preparation, and then at her first job at a low-income school in Brooklyn, New York, where teacher training and resources were slim.

Murray earned a master’s in education from Queens College-CUNY. At Penn GSE, she pursued a doctorate with a focus on mathematics education, delving into “how society, culture, and policies impact educational systems and vice versa,” she says.

“My mission was to really enhance my expertise, so I could go back into the school district and really provide educational opportunities for a diverse population,” she says.

Murray also has a graduate certificate in advanced education leadership from Harvard University. In 2017, she was the recipient of the Ethel and Allen “Buddy” Carruth Sustained Leadership in Education Award from Penn GSE.

The key to educational success, Murray argues, is for students to have preparation, whether formal or informal; access, which includes both the knowledge of the possibilities and a practical means to gain entry to educational institutions and professions; and resources, both financial as well as mentoring support.

Those three key learning pillars come from teachers, she says. But teachers must be properly trained to provide them, which is why Murray focuses on teacher education in her day job and in her role as a faculty member in the Penn Literacy Network, an evidence-based preK–12 professional development program housed at Penn GSE, and through professional organizations such as the National Network of State Teachers of the Year and Phi Delta Kappa, whose Educators Rising program supports diverse youth interested in teaching careers.

“The greatest impact on a child’s education is within the actual classroom,” she says. “If we don’t change and improve classroom practice, all the rest of our efforts will be moot.”

"The teaching strategy is to get to know your students, so they can see aspects of themselves and learn about themselves."

LETTING STUDENTS LEAD THE WAY

Kimberly Hee Stock, GED’05

Education trends may come and go, but Kimberly Hee Stock holds fast to the one truth she says any good teacher knows:

“You really try to get out of the way of students as much as possible,” says the 2021 Delaware Teacher of the Year, who lives in Wilmington. “When students are creating and taking charge of learning in the classroom, that’s true learning.”

Stock learned that lesson early, when she became a high school English teacher after graduating from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in 1996 with a bachelor’s in secondary education. A veteran teacher introduced her to the Socratic seminar, in which students read thought-provoking material and prepare questions and comments that they genuinely care about. Those questions and comments are then used to lead discussion.

Since discovering this approach, Stock has refined the method, fostering “genuine learning” by building trust and creating a safe space for self-reflection and goal setting, she says.

After a few years in the classroom, Stock enrolled in the Education Policy program at Penn GSE to earn her master’s, specializing in recruitment and retention and DEI, then left teaching to focus on her family for several years. In 2014, she joined the Claymont Community Center, where, she says, she helped establish the area’s first adult education program. She credits Penn for giving her the confidence to believe in herself and “think big.”

In 2016, Stock returned to the classroom as an English- learners (EL) and language arts teacher at the high-needs McKean High School in Wilmington, Delaware, where she works mostly with Spanish-speaking students seeking to gain proficiency in English. Stock again thought big, she says, proposing a more rigorous, inclusive curriculum for EL students.

For one unit, Stock taught The Book of Unknown Americans by Delaware native Cristina Henríquez that includes the story of two teenagers with immigrant roots coming of age. Students Zoomed with the author, asking questions in Spanish.

“You’re talking about kids who have been marginalized,” she says. “For them to see themselves in characters that look like them, that’s so powerful. That’s DEI.”

Stock’s diversity work resonates with her experiences growing up as an adoptee and Korean American in Nebraska, where, she says, she “didn’t see herself. I know how that feels. I want different for my students.”

The focus on prescribed curriculum makes individualizing lessons challenging, but Stock says she’s committed. In 2020, she earned a master’s from the University of Delaware in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages. Last year, Stock was elected to the Brandywine School District Board of Education on a DEI platform.

“It’s a constant, ‘How can I make what’s going on in my classroom more genuine?’” she says. “The teaching strategy is to get to know your students, so they can see aspects of themselves and learn about themselves.”

BUILDING DEI INTO STEM LEARNING

Justice Toshiba Walker, GEN’12, GR’19

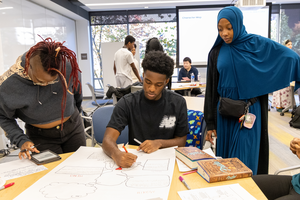

Justice Toshiba Walker, a learning scientist, assistant professor of STEM education at the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP), and principal investigator of the ABC Learning Lab, designs spaces where nontraditional approaches to science are encouraged and implicit biases are broken down.

“Much of my work is about disrupting structures that exclude or privilege dominant ways of learning and doing,” he says, “and creating learning experiences that are accessible and culturally relevant to learners.”

After graduating from the University of Miami (FL) in 2005 with bachelor’s degrees in biology and English literature, Walker worked as a science teacher for nearly a decade. One of his go-to lab activities involved gel electrophoresis, a technique used to separate DNA fragments by size. Rather than focus on abstract biology, Walker used a step-wise, hands-on approach, in which high school students conducted gel electrophoresis on a sample of their own DNA.

“For kids to have done it themselves, to see their genetic material touch the gel is powerful—and legitimate practice,” he says. The activity added depth to the biology curriculum, serving as a springboard to talk about DNA fingerprinting, crime scene investigations, and other popular topics.

Such activities, Walker says, are central to his teaching philosophy: “Give learners an experience that helps them feel a sense of self-efficacy. I feel it’s sometimes more important to have a good experience than meet a benchmark. If a person believes in themselves, that’s a game changer.”

Three years after earning his master’s in engineering biotechnology from the School of Engineering and Applied Science at Penn, Walker returned in 2015 for his doctorate in teaching, learning, and teacher education from Penn GSE. His thesis focused on developing a biomaking curriculum, in which students create genetically modified organisms (GMO), explore the emerging field of synthetic biology, and then design, bake, and market snacks that incorporate the GMO. FirstHand, a Philadelphia-based program of the University City Science Center that supplements STEM learning for middle and high school students, adopted the hands- on, student-driven curriculum.

At UTEP, Walker is researching culturally relevant curriculum design to engage learners. In “Coding Like a Data Miner,” a demonstration project funded by the National Science Foundation, underrepresented high schoolers will use cutting-edge techniques to scrape data from Twitter and analyze public sentiment around hashtags of personal interest. “This is data science,” he says. “Here, we say, ‘Pick your pursuit.’ Typical data science curriculum doesn’t do that.”

Ultimately, Walker says, new technologies must consider DEI at “the forefront, rather than as an afterthought.”

“If we’re to make any changes in disrupting the inequities that happen in the economies that develop under these technologies,” Walker says, “we have to be intentional early on, and it has to be multipronged, not only at the level of teacher practice, but also in the research that we’re carrying out and the design we’re using. Imperatively, we have to begin with learners, meet them where they are and pay close attention to—and value—what matters to them.”

“I feel it’s more important to have a good experience than meet a benchmark. If a person believes in themselves, that’s a game changer.”

USING DATA TO IMPROVE STUDENT OUTCOMES

Alexis Zhao, GED’13, GED’22

Growing up and going to school in Philadelphia, Alexis (née Schmidt) Zhao saw firsthand the highs and lows that education can afford. Zhao says she received a rich education with many hands-on learning activities, graduating from the university preparatory magnet Central High School in Philadelphia before heading to Drexel University to study psychology. But her siblings, she says, attended neighborhood schools with little exploratory education, and eventually “dropped out and got into not- positive things . . . I saw the inequities in Philadelphia schools.”

Witnessing such bifurcated opportunities instilled in Zhao a passion for equitable education.

Today, Zhao is a school-based teacher leader at the K–8 Chester A. Arthur School in South Philadelphia. A two-time Penn GSE graduate, she says she strives to create equitable education experiences through a focus on relationship building and hands-on projects that engage all students.

“I believe so much in the ability of our kids in the city,” says the former math and science teacher and current math coach who lives in Northeast Philadelphia. But, too often, she says, that ability is stifled by a shortsighted, testing-heavy teaching approach.

“Teachers are constantly asked to prove student achievement with data,” she says. “Kids take tests and tests. But the data isn’t being looked at to plan for instruction.”

Zhao began her teaching career in Northwest Philadelphia at K–8 Roosevelt Elementary School through Teach for America, earning a master’s in secondary education from Penn GSE at the same time. In 2021, Zhao returned to Penn GSE, completing a master’s from the School Leadership Program (SLP) in 2022.

As part of SLP, students complete a yearlong practitioner research project. Seeking to put data to use on behalf of students, Zhao’s project focused on the effect of teacher collaboration on practice when informed by standardized test data.

While enrolled, Zhao’s commitment to proactive data application continued as she held a principal-training internship and was an interventionist with math teachers during the 2021–22 school year. In one instance, she helped a fourth-grade teacher group struggling students by skill set by analyzing data and diagnostics from STAR and i-Ready, two computer-adaptive tests that gauge reading and math skills

to help educators assess students' strengths and weaknesses and inform instruction. Zhao and the teacher co-taught and worked together to develop a plan based on those learnings. Reflection, she says, led to “switching the groups up if we saw different needs or strengths, or re-evaluating how to teach the skills.” This school year, Zhao plans to do similar work with all of Arthur’s teachers.

Now, Zhao is pursuing a certificate in project-based learning from the School’s Center for Professional Learning.

And as passionate as she is about using data to guide lesson planning, Zhao has also strived at each stop in her teaching career to promote equity through her teaching.

At Chester A. Arthur, Zhao co-taught a fourth-grade unit on the environment in which students collected water samples from their homes and school water fountains and bathrooms. They tested for lead and other contaminants and analyzed data. They then wrote letters to City Council, advocating for clean water in schools and in homes across the city.

She also helped implement a restorative justice program and positive-behavior system for seventh graders that, she says, decreased out-of-school suspensions.

“In the morning meeting, we taught kids how to express themselves in words,” she says. “We did lots of one-to-one mentoring and relationship mending.”

Her time at Penn GSE, she says, reinforced her commitment to equity in education and “to be the change you want to see, to really just double down on the importance of relationships and grounding yourself in the research and always being a learner.”

This article appeared in the Fall 2022 issue of The Penn GSE Magazine.

Media Inquiries

Penn GSE Communications is here to help reporters connect with the education experts they need.