This story originally appeared in the Spring 2021 print edition of The Penn GSE Magazine.

by Lini S. Kadaba

How do young people learn about the responsibilities and possibilities of life in a democracy? To become active and informed citizens, they must discover how to think critically about the day’s issues and engage with their communities. Here, four Penn GSE alumni share the innovative ways they are advancing citizenship education by preparing students to participate in U.S. civic life. Whether by teaching civics and government, implementing district-wide curricula, creating learning experiences outside of the classroom, or engaging undergraduates in community service, these alumni are drawing upon their studies at Penn GSE to educate and nurture the next generation of citizens.

Bringing History to Life

Often, civics gets defined as the nuts and bolts of government, the contributions of familiar figures such as Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, and the importance of voting and jury duty. “That can come across as, ‘Eat your broccoli,’” says Adrienne G. Whaley, GED’08, director of education and community engagement at the Museum of the American Revolution (MoAR) in Philadelphia. At MoAR, the governmental and historical basics are acknowledged, but the emphasis is on bringing to life the diverse people and complex events that led to a new country and its democratic form of governance. The aim is to ensure that the nation’s “ongoing experiment in liberty, equality, and self-government” endures, according to the museum’s mission statement.

“The museum wanted to recognize a story not about heroes and villains, but about many complicated people,” says Whaley, whose Penn GSE master’s thesis in the Teaching, Learning, and Leadership program focused on teaching and learning Black history outside the public school classroom. “People were making decisions on complex issues without knowing what the outcome would be, and struggling with the distance between ideals and realities for themselves and for others.” At MoAR, she oversees educational programs for students, teachers, families, and general audiences and leads engagement efforts for Black communities.

Exhibits highlight a diversity of individuals who lived through and contributed to the Revolution, including women, free and enslaved people of African descent, Native Americans, Europeans of many stripes, and members of varied social classes and religions. “Through Their Eyes,” a field trip program Whaley designed, encourages students to imagine how people thought and felt at the time, and why they may have behaved as they did. Each student receives a card depicting a real person from the era (for example, one features a five- year-old boy who was enslaved by Thomas Jefferson), and museum educators weave these stories into discussions of artifacts and images.

“The museum wanted to recognize a story not about heroes and villains, but about many complicated people.”

An important aim is to show that the Revolutionary era launched debates about freedom and equality that continue today. “If we can help visitors understand the complexity of that moment, then that makes them better prepared to understand the complexity of every other moment in American life that has come afterwards,” says Whaley. She reports that the tour engaged approximately seventy thousand school children each year prior to the pandemic and has since broadened its geographic reach through a virtual format.

In addition to offering a variety of tours, workshops, and programs, MoAR also creates resources for teachers to help students develop skills practiced by historians. Those skills include critical thinking, active listening, and empathy—the “essence of good citizenship,” Whaley argues. When making decisions through voting, jury duty, or other forms of civic participation, she says, “people have to be willing to grapple with the fact that people have different experiences from themselves, with the fact that everybody’s perspective is different. If we can practice empathy, we can consider both our rights as individuals as well as our responsibilities as members of larger communities.”

Inspiring Active Participation

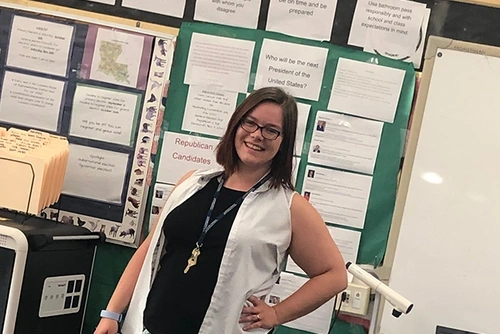

For Civics and AP Government teacher Sarah Cannon-Straight, GED’14, a passion for teaching civics began at Penn GSE in the Education, Culture, and Society program. Initially interested in U.S. history, she shifted her focus while researching her master’s thesis about the decreased role of social studies in school curricula, particularly in districts in low-income areas. She learned that an emphasis on preparing students for standardized testing often squeezes out civics, which is not assessed. For her it was an eye-opener.

“If you lose the civics component of social studies, when students become adults, they don’t know how to vote and they don’t know how to engage,” says Cannon-Straight. “We were creating this generation of students who were not educated on how the government works and how they can participate.”

As cultural studies department head at the New Orleans Charter Science and Mathematics High School (SciHigh), an open-admission public charter school in Louisiana, Cannon-Straight has developed creative curricula for her Civics and AP Government classes. Her focus is on hands-on exercises and connecting course content to students’ lives, with the ultimate goal of encouraging them to participate and seek change. “Civics is a ‘doing’ subject,” she says. “You learn a skill. Then you go vote. You go protest. You write your senators.” On alternate days, and in a virtual classroom during the pandemic, Cannon-Straight begins class with the day’s news. Recently, clips about the power grid crisis in Texas provided an opportunity to discuss how state and national authority are divided in the United States. “None of that was on the lesson plan for that day,” she says. “But it’s worth spending fifteen minutes on current events. You’ve got to make class time relevant.”

“If you lose the civics component of social studies, when students become adults, they don’t know how to vote and they don’t know how to engage.”

With that aim of relevance, Cannon-Straight brings in guest speakers (a city court clerk, a local candidate running for office) and prepares simulations in which students act out court or foreign policy procedures. She also has students pick a city woe, such as potholed roads, and investigate solutions, from the source of infrastructure money, to how resources are allocated, to the role of voting and local representatives. She encourages her students, many of whom turn eighteen while she’s teaching them, to register to vote.

“It’s about giving them skills, teaching them how to engage,” says Cannon-Straight, who was named the school’s 2020-2021 Teacher of the Year. “How are we ever going to enact change if we don’t have people who understand how the system works?” she asks. The payoff comes in the moments when graduates message her that they voted, show curiosity about what a jungle primary means, or work to get out the vote with a nonprofit. “Those are the connections that bring me a lot of joy,” she says. “I just need one of them to run for office.”

Lifting Up Student Voices

In a year that brought a global pandemic, heightened awareness of racism and oppression, and significant mental health challenges, the District of Columbia Public Schools found that a new curriculum was in order. The result is the “Living through History” unit that launched under the leadership of Melissa M. Kim, GRD’09, deputy chancellor of social, emotional, and academic development. The unit opened the school year for the district’s approximately fifty thousand pre-K–12 students and provided context for the dual pandemics of COVID-19 and racism to help students make sense of their experiences during tumultuous times.

“Educators need to be both content experts and also human development experts,” says Dr. Kim, a graduate of Penn GSE’s Mid Career Doctoral Program in Educational Leadership. “I think kids should be just as fluent in how they feel, how they respond to stress, as we expect them to be in math and reading.”

As the district’s 117 schools operated online due to the pandemic, the “Living through History” unit encouraged students to share their perspectives and apply academic knowledge to discuss the current era and create a variety of projects. A number of the resulting videos, songs, works of art, public service announcements, and time capsules have been featured on the Smithsonian Learning Lab website.

“We’re trying to redefine civic education,” says Kim. From the start, the new curriculum addressed the virus’s unequal impact along racial and socioeconomic lines and presented public health as a civic responsibility. In the wake of the siege on the U.S. Capitol, the district quickly provided teachers with resources to discuss the threat to democracy and the difference between insurrection and protest.

A main goal, Kim says, is to develop citizens who notice patterns of inclusion and exclusion in society and take action to address concerns, for example, by writing letters to Congress. “What I think civic education should address at its heart is how we can work to include people,” says Kim. “How do we get students to be reflective enough to participate in the creation of a better world?”

Inclusion has long interested her. Growing up as a Korean American immigrant and non-native English speaker often made her “feel outside of the dominant American culture,” says Kim. She wrote her Penn GSE doctoral dissertation on segregation and the experiences of students transitioning from racially homogenous elementary schools to racially diverse middle schools.

“What I think civic education should address at its heart is how we can work to include people.”

Kim reports that under her leadership, the school district has worked to create a culture of inclusion by putting student voices at center. For example, the redesign of two underperforming schools included extensive input from students. In addition, at the district level, long-term suspensions were reduced through alternative approaches that help students learn to share space and express needs and wants effectively.

While Kim emphasizes that the curriculum and initiatives are works in progress, she sees a positive impact. “We’ve invested a lot of time in engaging students,” she says. “What I do know is that they’re in a much healthier place as a result.”

Finding Common Ground

To David Grossman, GR’04, founding director of Penn’s Civic House and Civic Scholars Program, one goal of civic education is to find shared values amidst difference and division. “It’s important, as we’re an increasingly diverse and increasingly stratified world, that we work at understanding what it is we share in common,” says Dr. Grossman, also a Penn GSE adjunct assistant professor in the Higher Education division. He sees Civic House, located at 3914 Locust Walk, as an important way in which Penn helps students learn to work toward a more equitable society.

Penn established Civic House in 1998 as a hub to build upon existing community service programs, with Grossman as director and a mission to “promote service as a means of preparing students for their roles as citizens and leaders,” according to Civic House’s charter. Today, Civic House is home to a range of initiatives that engage students in service and advocacy. Its work aims to promote mutually beneficial collaborations between Penn and the communities of West Philadelphia, other Philadelphia neighborhoods, and the larger world.

That mission is about much more than mere volunteer hours, according to Grossman. “It’s about providing opportunities, both formal and informal, for students to learn about, to explore, and to practice what it means to be part of a broader society, and in that process, ask challenging questions of themselves,” he says. Programs attract hundreds of students each academic year.

Highlights include the West Philadelphia Tutoring Project, through which Penn students provide free tutoring to local K–12 students, and the Community Engagement Internship, which provides funding for Penn students to undertake internships at community organizations, among them Bread & Roses Community Fund and VietLead. In addition, the signature Civic Scholars Program recognizes up to fifteen Penn undergraduates in each class with a special four-year experience integrating civic engagement and scholarship. These and other Civic House programs adapted to operate virtually during the pandemic.

Community partnerships are key to the work of Civic House and were the topic of Grossman’s doctoral research in Penn GSE’s Education Policy program. Through studying the efforts of nonprofits to address longstanding issues in West Philadelphia, such as racial and economic inequity, he concluded that the best chance to improve outcomes arises from a shared understanding between community partners.

“It’s about providing opportunities, both formal and informal, for students to learn about, to explore, and to practice what it means to be part of a broader society.”

“It’s important that we not position ourselves as experts, but rather value the local community as having assets, such as vital experiences and knowledge of their own, that should drive partnerships,” he says. His hope is that such a model of civic engagement will strengthen our democracy through greater connection and collaboration.

“We have to be walking through the world in a way that we understand ourselves as part of the whole,” Grossman says. “Then we’re going to be better members of our communities. That is the point of this work.”

This article appeared in the Spring 2021 issue of The Penn GSE Magazine.

Media Inquiries

Penn GSE Communications is here to help reporters connect with the education experts they need.