by Lini S. Kadaba

The novel coronavirus pandemic and renewed calls for social justice in the wake of police brutality have permeated every facet of life—and the role of educators and leaders in the lives of learners worldwide is more important than ever. Here, four Penn GSE alumni share the challenges they have faced in their work and the many ways their Penn GSE experience has helped them chart a promising path forward.

Developing Change Agents in Schools

When The School District of Philadelphia moved to virtual learning this spring, Rahshene Davis, GED’03, assisted principals as they marshaled staff volunteers to ensure each student in the District’s Learning Network 2 got a Chromebook. While some students already had school-issued devices, many did not.

Davis oversees the thirteen K–8 schools in West Philadelphia as assistant superintendent of Network 2, where most schools serve a low-income population and students of color make

up the vast majority of the student body. While the successful distribution of technology this spring made her schools better prepared for a fully virtual start of the new academic year, for Davis, the circumstances of COVID-19 and civil unrest around race have coalesced, with the pivot to distance learning spotlighting disparities.

“Now that inequities are front and center, what are we going to do about it?” asks Davis, who earned her master’s in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages at Penn GSE.

“The role of principals is ever more crucial in these times of COVID and of students speaking out about racism and bias and having conversations with leaders to seek change.”

Her answer is to continue her focus on developing the most influential “change agents” that schools have: principals. Having begun her career as a teacher at the Henry C. Lea Elementary School, part of Network 2, Davis went on to work as a national literacy consultant and to study school reform. Her wide-ranging experiences taught her the importance of school principals, and she took on the role at University Heights Charter School in Newark, New Jersey, earning recognition for breakthrough student achievement gains.

Now, as assistant superintendent, Davis mentors Network 2’s principals, drawing inspiration from her work as a current student in Penn GSE’s Mid-Career Doctoral Program in Educational Leadership. “The role of principals is ever more crucial in these times of COVID and of students speaking out about racism and bias and having conversations with leaders to seek change,” she says.

Drawing upon her timely thesis, which considers the anti-racist leadership practices of Black district-level leaders who seek to dismantle systemic racism in schools, she is making anti-racist education a priority. She has shared a self-care checklist by Dr. Howard Stevenson, Constance Clayton Professor of Urban Education at Penn GSE, for navigating racial stress. She sees the Responsive Math Teaching project, led by a team from Penn GSE in Network 2’s schools, as an important partnership that fosters equity by promoting high-quality math instruction for students of color. “The program is aligned with the instructional vision that I have for my network, which is to improve teaching and learning,” she says. To help principals navigate the many changes they have faced, she shared Penn GSE Professor of Practice Sharon Ravitch’s “flux pedagogy” for leading through uncertainty, and Dr. Ravitch joined an April Q&A with principals via Zoom. In addition, Davis is helping principals to harness the benefits of Zoom to engage parents in new ways.

“I’m helping leaders see there are things you can continue to do even when we go back to face-to-face,” Davis says. “We should stay connected.”

Keeping a Community Inspired

In the United Arab Emirates, Navin Valrani, W’93, GED’18, CEO of Arcadia Education, has tackled virtual learning and reopening plans for Arcadia School, the first in a planned series of private schools meant to improve the K–12 educational landscape for children in Dubai.

“With the city of Dubai being one of the early movers in the shutdown of schools, we came up with an innovative device loan program within hours to ensure that every child at Arcadia could engage in the school’s distance learning program,” he says.

Perhaps the school’s focus on innovation and mindfulness made it well suited to adapt. Opened in 2016 by Arcadia Education, a venture between Mohan Valrani and the Al Shirawi Group, Arcadia School combines a British curriculum with an emphasis on student happiness through yoga, nutrition, and mindfulness. Throughout the transition to virtual, he says, the guiding question for both students and staff was, “What did we learn from this experience that made us better human beings?”

At the pandemic’s height, teachers collaborated through regular virtual forums and senior leadership made themselves available to parents. In a weekly Zoom call with students, Valrani fielded questions about the virus and on race relations in America. The school also cut its fees by 20 percent and worked with parents who lost jobs and couldn’t afford tuition.

“It’s time to lift ourselves up and know there’s an entire community out there that looks at us every single day for inspiration.”

Lessons were pre-recorded for younger students, but the school soon incorporated synchronous instruction as many missed the connection with peers and teachers, Valrani says. For older students, up to half the classes were live. “This put tremendous pressure on the teachers,” he says. “They have been the true heroes.”

Valrani, who grew up in Dubai, attended Wharton as an undergraduate. Once home, he was tapped to oversee the Al Shirawi Group’s construction and development. Later, his additional role as CEO of Arcadia Education brought him back to Penn to continue his own education. Pursuing his master’s in education entrepreneurship at Penn GSE, he says, helped him shape Arcadia School’s mission of producing students who “go on to become selfless, tolerant, and unifying citizens in society.”

With a new academic year underway, Valrani has returned to Penn GSE—remotely—as a student in the Penn Chief Learning Officer doctoral program. Arcadia is implementing in-person instruction with protections that include UV technology in the HVAC system, thermal imaging cameras at entrances, and classroom cameras for those more comfortable learning from home.

In times like these, Valrani says, educators can take solace in the power of their profession to make the world a better place. “When the chips are down, as they have seemed to be in the past several months, it’s time to lift ourselves up and know there’s an entire community out there that looks at us every single day for inspiration,” he says.

Collaborating to Meet Students’ Needs

When public schools in Washington, DC, moved online, English language learner teacher Megan Tribble, GED’11, was skeptical about connecting virtually with her students at Lafayette Elementary School.

“I didn’t know how I would teach young children through a computer,” says Tribble, a member of the school’s Academic Leadership Team and Racial Equity Committee. “But pretty much everything exceeded my expectations.”

To navigate the impact of COVID-19 on learning and equity both then and now, Tribble has relied on strong collaboration and critical thinking—skills she credits to her time earning her master’s in teacher education at Penn GSE. Her teaching placement at the Penn Alexander School, she says, gave her practical experience and professional mentoring, while her coursework provided “the space to discuss large-scale issues of educational equity and policy solutions for these challenges.”

At Lafayette, where an insensitive lesson on slavery caused concern last year, she reports that she and others had already been working to place a year-round focus on issues of racial inequity.

The coronavirus posed additional challenges, ones Tribble likens to building a plane and flying it at the same time. When the DC schools closed on March 13, spring break was moved up—but teachers continued to work, “hammering out plans for how to create virtual learning that mimics in-person school as closely as possible,” Tribble says. A framework of daily meetings via Microsoft Teams encouraged collaboration.

“The shift to distance learning was far from perfect. Almost every day I logged off Microsoft Teams wishing so badly I could just see my students in real life. But with strong collaboration and a growth mindset, schools can create a robust and positive learning experience. I saw it happen.”

“We learned through trial and error,” Tribble reports. Take the morning meetings that began each student’s day. Tribble and colleagues quickly realized the necessity of the mute and unmute buttons to keep control of the class. Small-group reading was dropped at first, but soon reinstated through virtual breakout rooms known as channels. With the school library inaccessible, Tribble helped organize the purchase of books with the help of the Home and School Association, and she and others delivered them to children.

Meanwhile, student clubs helped maintain social ties, and the school formed a Social-Emotional Learning Committee. Tribble spent time brainstorming solutions with academic leadership, seeking to balance the expectations of families and teachers. A spreadsheet tracked each student’s needs, including social-emotional learning, family needs, and academics.

Tribble was pleasantly surprised to find that some of her students fared better online than in the classroom, no longer distracted by classmates. “I saw so many of my English learner students make tremendous academic progress,” she says. Overall, she notes, feedback from parents has been positive.

“The shift to distance learning was far from perfect,” she says. “Almost every day I logged off Microsoft Teams wishing so badly I could just see my students in real life. But with strong collaboration and a growth mindset, schools can create a robust and positive learning experience. I saw it happen.”

Propelling Innovation in Higher Education

Despite the challenges of current times, Mahesh Daas, GRD’13, president of Boston Architectural College (BAC), sees opportunity for higher education innovation in both the need for social justice and the impact of the coronavirus.

Appointed to his current role in 2019, Dr. Daas has presided over a mission that has only increased in relevance—in his words, to “provide diverse communities access to professions that are acutely in need of better inclusion and diversification.” Consider, he says, that only 2 percent of licensed architects are African American, and a fraction of a percentage point are African American women. “That is how anemic the professions are in terms of diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

The 675-student BAC largely meets its goal, Daas says, through an education model in which students work a practicum from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. at one of eighty-one partner firms and then attend classes, sometimes until 10 p.m., getting assessed on both fieldwork and academics. Students (Daas reports an average age of 28.5 years and 45.8 percent people of color) earn while they learn, which can make college more affordable, and an open admissions policy helps reduce barriers of access.

“We were talking about social justice well before all these issues became national and international discourses,” he says. “That is why our mission is what it is.”

“When the protests began to happen, or even when the pandemic broke out, in a way our vision and strategy aligned with what we saw emerging. We just had to accelerate, invest more.”

When COVID-19 struck, the college already had 43 percent of its programs online, which made for an easier transition, he says, noting that BAC also has the first primarily online master’s program to earn accreditation. Most students continued their practicum placements remotely, but those laid off were assigned to community-based projects, such as developing site proposals.

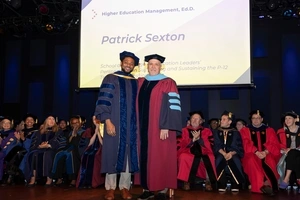

Soon after his arrival, Daas began a strategic plan, often seeking advice from his cohort in Penn GSE’s Executive Doctorate in Higher Education Management program. The plan includes social justice, which encompasses diversity, equity, and inclusion, as one of six tenets of BAC’s “Vision Hexagon.” He envisions social justice initiatives cutting across all aspects of the college—the curriculum, extracurricular activities, research, and institutional structures—supported by the resources to make a difference.

“When the protests began to happen, or even when the pandemic broke out, in a way our vision and strategy aligned with what we saw emerging,” he says. “We just had to accelerate, invest more.”

Daas also has emphasized nonviolent communication developed by psychologist Marshall Rosenberg as a way to improve organizational culture, implementing faculty and staff workshops on the approach that puts empathy at its center.

“The world has shifted,” he says. “Our way through these times is through innovation, and not by managing the crisis to go back to models and paradigms from before the pandemic.”

This article appeared in the Fall 2020 issue of The Penn GSE Magazine.