Faculty Expert

-

Sigal Ben-Porath

MRMJJ Presidential Professor

Policy, Organizations, Leadership, and Systems Division

Congress is launching an impeachment inquiry of President Donald Trump, and the story will likely dominate the headlines—and divide the country—for months to come.

Which is why teachers should address the impeachment inquiry directly.

Talking about significant news is one of the key ways that kids learn to be civically engaged, says Penn GSE’s Sigal Ben-Porath, a political philosopher and expert in civic education. But talking politics isn’t easy. Ben-Porath says teachers should have clear and specific goals for a lesson about impeachment, and they should tether the lesson to other educational objectives.

What does that look like? Here’s what Ben-Porath says you should think about:

Don’t fear the controversy, lean into it

Educators sometimes shy away from political issues. But students, especially middle and high school students, will have read about the inquiry or seen it discussed on TV. Controversial issues drive civic engagement, Ben-Porath says, especially among young people who might see this as their first chance to engage with politics.

While history and civics classes are a natural place to discuss impeachment, language arts teachers can build important lessons around rhetoric or media coverage. A homeroom teacher can even do a quick review of the latest developments.

“We are in a historic moment,” Ben-Porath says. “This is a unique chance to engage students, and we shouldn’t let it pass.”

Dig into the facts

Students are reading the headlines. Ben-Porath suggests helping them dive a little deeper by exploring questions like:

- What are the powers of the presidency related to foreign policy?

- What is a whistleblower? Why does the law protect them?

- How does impeachment work?

- What is Congress’s oversight role of the executive branch?

- What does it mean when the president is impeached?

- What are the different roles played by the House and the Senate in an impeachment proceeding?

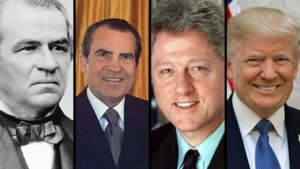

- What happened in the impeachment cases of Andrew Johnson, Richard Nixon, and Bill Clinton? For this final question, don’t just look at the historical record, since it can present a settled narrative. Shocking surprises can feel inevitable. If students read what people defending and attacking these presidents wrote at the time of those impeachment proceedings, they will have a better understanding of how chaotic and unpredictable key events in a nation’s history can be. Here’s a guide for creating such a lesson.

Get people talking

Don't just lecture. The impeachment inquiry is dominating the public discourse. Reflect that with a whole-classroom discussion.

“Classroom discussions get people thinking and practicing different civil roles,” Ben-Porath says. “They are a way for students to learn to engage and debate without fighting.”

Want more ideas for keeping a discussion flowing? Try this guide from Penn GSE Dean Pam Grossman.

Want more advice for the classroom? Subscribe to the Educator's Playbook newsletter

Make the time

Maybe you can devote an entire class period to these questions. Maybe you can only set aside 15 minutes some time in the next two weeks. Either way, Ben-Porath says you should use the news in your lessons.

Because the story will continue to unfold, plan for regular check-ins, even if only for 10 minutes a week. Encourage your students to ask follow-up questions. Let them guide your next discussion.

Consider other views, as long as they are grounded in facts

It’s important for a teacher to present diverse viewpoints, and this is especially true in communities with dominant liberal or conservative majorities.

Offering a minority viewpoint creates a welcome place for a student who might not want to advertise that they disagree with their peers. More importantly, students need to be able to unpack why someone might disagree with them on an issue like impeachment.

“In a polarized time like this one, it’s crucial to learn how to consider someone else’s position,” Ben-Porath says. “How can we assume good faith on someone else’s part, even if we reach opposite conclusions to the same question?”

Keep a simple ground rule: Opinions are a part of politics, but classroom discussions must be grounded in proven, relevant facts.

Take it beyond the classroom

Your students are participants in this democracy. Challenge them to get involved.

Have students research their own representative’s stance on impeachment. Ask what your students might do to convince the representative of their views. Encourage them to reach out to elected officials or write a letter to the editor of your local newspaper.

Should I say what side I’m on?

Teachers often wonder if it’s appropriate to tell students their political views. Ben-Porath says:

“Generally speaking, it’s fine to disclose your political views as long as you clarify your openness to other views — and affirm that openness with your actions. Consider disclosing your views an option, not an obligation. Not every teacher feels secure talking openly, especially if their opinion is in the minority in the community.”

Subscribe to the Educator's Playbook

Get the latest release of the Educator's Playbook delivered straight to your inbox.

Media Inquiries

Penn GSE Communications is here to help reporters connect with the education experts they need.