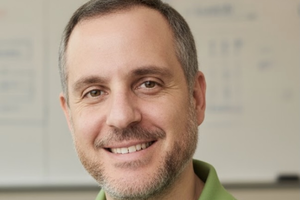

The Penn GSE community is mourning the passing of groundbreaking alum and former Philadelphia schools superintendent Constance E. Clayton, remembering her fierce commitment to students in what was then the nation’s fifth-largest public school district and her transformative impact on the School. Clayton died last week at the age of 89.

“Her contributions will be remembered and cherished, and her impact will endure as a testament to her unwavering commitment to education and social justice,” said Dean Katharine Strunk. “Without question, Penn GSE is a better place because of her.”

A Philadelphia native, Clayton started her career as an elementary school teacher in 1955. She went on to earn her Ed.D. in Educational Administration from Penn GSE in 1981 before serving on the University’s Board of Trustees from 1984 through 1989. That overlapped with her time as the head of the School District of Philadelphia, where she had the distinction of being the first woman and first Black Superintendent, serving from 1983 until her retirement in 1993. During her transformative tenure, she was renowned for tackling a problematic budget without cutting student services, attracting local businesses to help equip schools with better resources, and establishing schools as the center of their communities.

“She believed every student deserves a good education, even if they come from difficult circumstances and challenging neighborhoods,” said Penn GSE’s Constance E. Clayton Professor of Urban Education, Howard Stevenson. “For her, you’re going to have to fight for them.”

The endowed professorship in Clayton’s honor was established at Penn GSE in 1992, just before Clayton’s retirement, with funding from the William Penn Foundation, Cigna, Vanguard, and PNC. The chair also had many small donors, which is unusual for a professorship—in fact, of the 66 total gifts, nearly half (27) were for $500 or less. That speaks volumes about Clayton's impact, said Stevenson, who also serves as the director of the Racial Empowerment Collaborative.

“A lot of people knew of her fight for children,” he explained. “And the people who gave were people who didn’t necessarily have a lot of money but knew the importance of her work.”

The chair made Clayton one of the first Black women in the U.S. to be honored with an endowed professorship. The first person to hold the Clayton chair and Stevenson’s immediate predecessor in that role was Professor Emerita Diana Slaughter Kotzin.

“She practiced what she preached,” Slaughter Kotzin said. “It would be a mistake to say she was not truly an activist. She was not [just] a philosopher or an academic, she was looking for ways to help kids who didn’t necessarily have it as well as she did.”

As superintendent, Clayton would take the time to write letters to individual students in the district congratulating them for their high academic achievement. Slaughter Kotzin remembers an administrative assistant who worked for her at Penn GSE who still had her letter from Clayton, a prized possession from her youth.

“[Clayton] wasn’t walking around carrying a flag, but she touched people at the most basic level,” Slaughter Kotzin said.

She also praised Clayton for being one of the first scholars to link early childhood education opportunities to later educational outcomes, helping to kick off the Head Start movement. Clayton wrote her dissertation on the topic and became a bridge between early childhood education and educational administration. The benefits of early childhood learning are now so well known, Slaughter Kotzin noted, that it’s difficult today to find children who haven't received at least some early education.

Under Slaughter Kotzin, the annual Constance E. Clayton Lecture was established. Clayton vetted every speaker selected, familiarizing herself with their background, extensively researching the topic, and finding its relevance to Philadelphia.

At one lecture given by Philadelphia’s superintendent at the time, Stevenson said he had brought students from the Jubilee School in West Philadelphia to attend. Clayton was unhappy with an answer the speaker gave to a question and jumped into the discussion.

“She stood up and said, ‘Maybe since these young people are here, maybe they have questions they’d like to ask their superintendent,’” Stevenson said. “She was more interested in the kids having their voices heard than in it being ‘her’ lecture.”

Stevenson and former Penn GSE Professor of Practice James H. “Torch” Lytle shared that Clayton “did not suffer fools.” Stevenson said Clayton had shared stories of politicians attempting to meddle with her leadership through favors, but she would refuse.

“She did not get along with political actors because she was focused on helping children in Philadelphia rather than self-promotion,” said Lytle, who served under Clayton in several roles with the school district, including deputy assistant superintendent, before becoming a superintendent in Trenton.

“She made sure that decisions and initiatives were debated, both within senior management and with teacher union leadership, and informally through her network of people she had worked with over the course of her career,” said Lytle. “There was never much doubt that what she was doing was in keeping with what the city needed and what the district needed.”

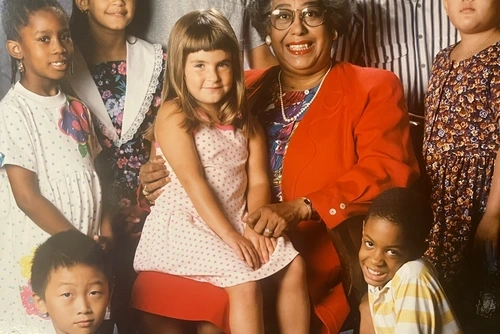

For example, Lytle cited a bussing initiative Clayton spearheaded for the school district to help desegregate it, which received “a lot of heat” from white parents in some parts of the city. But Clayton did not back off the plan.

“Within the district, there was a great deal of appreciation for how she went about this,” he recalled.

Lytle also praised Clayton’s “understanding that it’s teachers who do the work at schools and in school districts, and that needs to be kept in mind at all times.” After a number of tumultuous years of teacher strikes in the district, Clayton’s term ushered in an era of peace and stability. Under her leadership, there were no labor strikes or deficits.

Clayton also saw great value in teachers' professional development and put it back in the hands of individual schools during her tenure.

“I think Dr. Clayton was really proud to be a Penn GSE alum. Keep in mind that the number of women and African American students at GSE in her era was a lot different than what it is today,” Lytle said. “And she wanted to make sure that whatever development work she did was very legitimate and increased her efficacy as a leader.”

Clayton's legacy also continues in Penn GSE's Marcus Foster Fellowship. Clayton led the charge to establish the fellowship in 1984 to increase the number of full-time students of color at the School. It honors the memory of alum Dr. Marcus Foster, a nationally acclaimed Black educator who became the first Black superintendent of a large city school district in the U.S. before he was assassinated by a terrorist group in 1973.

Media Inquiries

Penn GSE Communications is here to help reporters connect with the education experts they need.