Faculty Expert

-

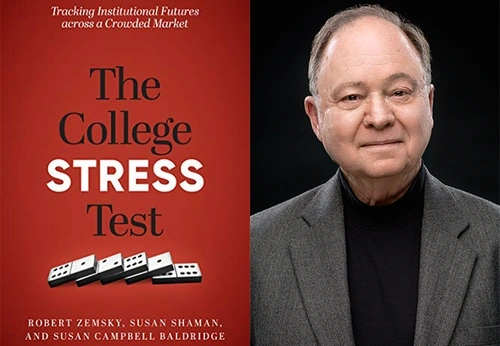

Robert M. Zemsky

Professor Emeritus

Released weeks before the first American COVID-19 cases were reported, The College Stress Test revealed how close many universities were to financial ruin — predictions borne out as colleges were forced to lay off employees, eliminate programs, and close their doors for good.

Co-author Robert Zemsky, a luminary in the field and a professor in Penn GSE’s Higher Education Division, spent the summer briefing university leaders, boards of trustees, system administrators, and policy makers on what’s coming next.

Here are the six trends Zemsky says will influence higher education decision making in 2021:

Leaders just might get real about the business model

The pandemic revealed that many college leaders didn’t fully understand how their universities operated as businesses. Or that “residual expenses” — profits made off services like room and board — balanced the books. In a typical case, a 1,200-student college earned $5 million in profit last year on these charges. There isn’t an easy way to recoup those losses.

Expect the leadership team — even the lifelong academics — to put these line items front and center in any discussion about opening online or in person, even at those schools dealing with COVID outbreaks this fall.

Tenured faculty will face a squeeze

What do tenured faculty dread more, a bigger course load or a pay cut? That’s the choice universities will soon face.

Zemsky says college leaders will have fewer options than they think to reduce non-academic costs. That leaves academic costs, where the first choice for many will be a faculty pay cut. But that’s the wrong choice, Zemsky says.

Instead, colleges should hire fewer adjuncts and up the required course load for tenured faculty.

The traditional curriculum could be transformed

In a traditional year, half the colleges in America lose at least a quarter of their freshman class. This was always an embarrassing educational failure, but the cash crunch is forcing colleges to see their retention problem as a revenue problem.

It’s time for colleges to get serious about transforming the traditional curriculum. Today’s students are smart. They can seek out information, collaborate, and create. But many of them don’t get excited by long reading lists. Zemsky says it’s time to update the curriculum to challenge students in a way that fits their learning styles.

The three-year degree could be adopted

Most American students don’t really need four years to earn a college degree. The three-year degree makes sense, both financially and academically, Zemsky says.

There was some buzz about moving toward three-year degrees a few years ago, but colleges didn’t feel an urgency to make the change. They will now.

Sports will dominate headlines … for all the wrong reasons

Major college football programs’ “will they/won’t they” drama captured the headlines this fall, but Zemsky says university leaders will have to focus on athletics throughout the year “for all the wrong reasons.”

The budgets of many colleges — even those that are never on TV — are entangled with their athletic departments in ways that are increasingly uncomfortable. The longer it’s not safe for most sports to play — and the longer the NCAA has to go without staging the televised events that subsidize small conferences — the more sports will bleed general funds.

Campus leaders will not be calling all of the shots

Before this year, college leaders enjoyed wide latitude to call the shots on their campuses. Not anymore. As many colleges in California learned this fall, a president’s plan to start classes in person might only get as far as the local health department.