Faculty Expert

-

Zachary Herrmann

Senior Director of Strategic Initiatives

Learning, Teaching, and Literacies Division

How do we transform teaching and learning to prepare students for the 21st century? And how do we move forward in a way that increases equity across education?

Pam Grossman, Penn GSE Dean, Zachary Herrmann, director of the Project-Based Learning Certificate Program, Sarah Schneider Kavanagh, assistant professor, and Christopher Pupik Dean, Senior Fellow, spent years examining one teaching approach that can answer both questions.

Their new book, Core Practices for Project-Based Learning, from Harvard Education Press, takes a deep dive into how a student-centered approach has the potential to empower students to be engaged citizens and take on modern challenges.

Grossman has dedicated her career to improving teacher training and professional development. This collaboration with fellow Penn GSE researchers is her latest effort to push the field of education to think about how teachers are prepared before they enter the classroom, and how they can continue to refine their skills.

Grossman and her colleagues lay out the practices and supports educators need to create deep learning experiences for their students. And they make an argument for why this is the time to bring PBL from specialty schools to the center of American education.

What is project-based learning?

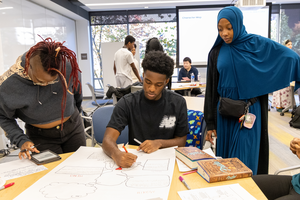

Broadly defined, project-based learning, or PBL, is a method of instruction that identifies a project or problem that students work on (often with peers), engages sustained inquiry, gets feedback and critiques that support revisions, shares the work with a wider audience, and then reflects on the learning that happened across the whole process.

For example, instead of two weeks of lectures about watersheds, an Earth Science teacher might assign their students to prepare a report for city council about the health of local streams that could be affected by a proposed development project.

The students will still learn what makes a healthy watershed and what can threaten that environment. But they’ll also visit the streams, perform water quality tests, analyze the data, and use it to contribute to a real conversation around a real problem in their community.

Project-based lessons can last a few days or stretch through the school year. They can be designed for any grade level or subject matter. And teachers can use PBL techniques to enhance almost any lesson.

What allows PBL to succeed in the classroom?

Project-based learning has a higher degree of difficulty than other forms of teaching. As one educator told the authors, “one of the biggest transitions for teachers into a PBL environment is to relinquish a sense of authority in order to support student voice in the classroom.”

In their research, Grossman and her colleagues worked with teachers, educational leaders, and curriculum designers to identify the core goals and practices of project-based teaching: supporting deep disciplinary content learning, engaging students in authentic work, supporting student collaboration, and building an iterative culture where students are always prototyping, reflecting, redesigning, editing, and trying again.

They also found that successful PBL teachers see themselves as learning along with their students, with every lesson being an attempt to improve upon the previous iteration.

Why is PBL having a moment?

PBL is not new. You can find examples of PBL teaching in American K-12 schools dating back more than a century.

But there are signs that the PBL approach is growing in popularity. Chicago Public Schools now require all students to engage in a service-learning project. Massachusetts mandates all public secondary schools in the state provide opportunities for students to engage in student-led civics projects.

Grossman, Herrmann, Schneider Kavanagh, and Pupik Dean argue that the current enthusiasm for PBL might reflect the fact that the approach is particularly well matched to ambitious twenty-first century learning goals of collaboration, creativity, communication, critical thinking, and flexible uses of technology.

As more jobs require teamwork and collaboration, PBL can provide an opportunity to develop these capacities alongside the cultivation of more traditional academic goals, including content knowledge and the development of academic skills.

While schools serving affluent students have been more likely to use PBL methods, the authors believe the approach can used to drive equity in American education. Through their research, they found examples in different cities, including Philadelphia, of students in poverty-impacted schools succeeding when offered these kinds of opportunities.

Grossman, a nationally renowned expert on teacher quality, and her co-authors researched their book before the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted education. But they believe the lessons are especially important at a moment when schools are trying to find a new way to serve students – rather than return to the old formulas -- because empowering students is at the very heart of PBL.

As one teacher told the authors, “the whole idea of project-based learning is to get the students to see that the work they do is important not just for learning but for the betterment of themselves, their community, and the society they live in.”

Media Inquiries

Penn GSE Communications is here to help reporters connect with the education experts they need.