Faculty Expert

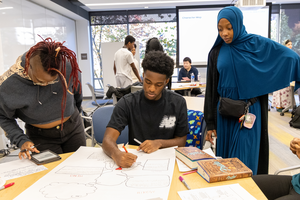

Educators from Penn GSE, the University of Pennsylvania, and across Philadelphia gathered both in-person and online this past week for “Teaching Independence: Bridging the Communications Gap,” a two-day symposium that took an in-depth look at the challenges of teaching the Declaration of Independence, the American Revolution, and the nation’s founding in the current political climate.

Co-organized by McNeil Center for Early American Studies Director Emma Hart and Penn Libraries Director of Programs and Senior Curator for Special Collections Lynne Farrington — along with Penn GSE and the Museum of the American Revolution — the symposium was the kickoff of America 250 at Penn, a series of programs being built by Penn Libraries to explore the country’s roots as we approach its 250th anniversary.

“We’re hoping that this leads to more events that discuss the issue of teaching independence broadly as, of course, the 250th anniversary of the Declaration looms in 2026,” said Hart. “And the goal for today and tomorrow is to bring together voices from across the educational spectrum, from K-12 teachers to universities and public historians.”

An Opening Roundtable

The roundtable which opened the symposium focused on the public debate surrounding the 1619 Project, how it relates to our understanding of the founding of the country, and the way American history is taught.

For context, Hart noted the Pennsylvania legislature is currently sitting on House Bill 1532, which aims to influence the way American history is viewed and relayed in classrooms across the state by limiting discourse on race and gender discrimination. The bill is similar to many such bills currently being debated in statehouses across the country.

Speakers were invited to discuss how they, as educators, teach the Revolutionary era of American history in such a fraught political environment. Those speakers included two representatives of Penn GSE:

- Ismael Jimenez, Adjunct Professor at Penn GSE and Social Studies Curriculum Specialist with the School District of Philadelphia

- Abby Reisman, Associate Professor in the Teaching, Learning, and Leadership Division

Confronting the American Myth

Jimenez, who taught African American history for 12 years and is currently working on rewriting the African American history curriculum for the School District of Philadelphia, noted that one of the very first questions that came up in the process was, “Was the American Revolution about slavery?”

“Of course, nobody agrees on that whatsoever,” Jimenez said. “But we thought it was a great essential question for students to wrestle with right off the bat.”

As such, students were shown letters submitted to the New York Times by prominent historians contesting the Revolution was, in fact, over slavery. They were also shown the response from the New York Times editors, which made the case that while it was debatable, the jury was still out on the significance of the role slavery played in the leadup to the Revolution. The goal, Jimenez said, was to show students they could approach history and look at the things that weren’t written down and weren’t settled and then come to their own conclusions.

The exercise was then repeated, this time asking students if the Constitution was a pro-slavery document.

“We’re not telling them the answer,” Jimenez said. “There’s not supposed to be an answer. It’s supposed to be a combination of looking at interpretive record materials and primary documents, then allowing students to contextualize the reality of that time period for themselves.”

Jimenez spoke on how frequently the teaching of American history turns into the teaching of mythology — and how it is important as educators to challenge people and get them to understand that American independence in the time of the Revolution was less about creating universal freedoms for individual members of society and more about an elite class wrestling for their own power and influence.

As students come to understand the context of the Revolution-era definition of American independence, he added, they begin to ask why they haven’t been taught these things before and why it all contradicts so thoroughly the stereotypical, flag-waving narratives they’ve seen since birth.

“I want them to understand that when ‘all men are created equal’ was written, that the majority of folks in this society were not free by our definition,” Jimenez said. “I’m talking about women. I’m talking about indigenous people. I’m talking about enslaved and non-enslaved Africans. I’m even talking about indentured whites, poor whites unable to scratch out a real existence in society.”

Understanding these inherent contradictions in the narrative of American freedom, Jimenez contended, is crucial to cutting through the mythology and getting a better grasp on the work of civil rights and social justice movements.

It also, he added, helps frame the current debates around critical race theory and the overall direction of the country. Constant attacks on honest efforts to inform and educate younger — and older — generations about the much more complex nature of American history than the one so deeply embedded into our societal narrative have left us in a precarious position.

“Our children are just a reflection of us,” he said. “We need to start being extremely intellectually honest with ourselves, our children, and each other. Look at the role we play as educated adults, as citizens. Even if the history is not written completely yet, we have a responsibility to write that history and allow our children the chance to think about these stories in real ways.”

The Interpretive Nature of History

Reisman opened her presentation by discussing House Bill 1532, noting the bill itself makes almost no mention of history or how history might be taught aside from one critical thing: it prohibits instruction in which an individual, by virtue of the individual’s race or sex, bears responsibility for actions committed in the past by members of the individual’s race or sex.

“This, of course, is the root of the problem, right?” said Reisman. “The potential discomfort or guilt that one might feel upon learning one’s ancestors did an awful thing.”

Reisman pointed out what many historians have pointed out: that culture wars like the backlash against the 1619 Project are cyclical, predictable, and have happened multiple times over the past century. The common thread running between them, she added, is they are triggered by an effort to question the narratives of American exceptionalism and triumph.

“When an origin story is considered sacrosanct, any challenge to it is sacrilege,” said Reisman.

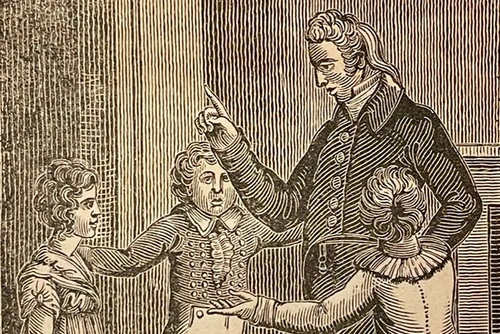

However, teachers do not need to wait for historians to challenge one another on the realities of our nation’s origin story to illustrate for their students the interpretive nature of historical documents and accounts. To illustrate, Reisman pointed to an example from a current American history textbook that looked at a passage written by John Adams about the Boston Massacre and the death of Crispus Attucks, a multiracial man who is regarded as the first American colonist killed in the American Revolution.

The quote as it sits in the textbook, Reisman pointed out, seemingly has Adams heaping praise upon Attucks and his bravery, painting a picture of a bold group of diverse individuals standing up to British soldiers. Unfortunately, the quote is carefully snipped out of a larger passage by Adams in which he is defending the British soldiers’ actions at the Boston Massacre and using race to paint Attucks as a violent, bloodthirsty instigator.

“The textbook made certain choices about how to extract Adams’s words — choices that we can question,” Reisman said. “Why might the textbook publisher have chosen to cut those specific phrases? What does including the redacted text force us to acknowledge about our history? How does it challenge our origin story?”

In the face of history texts which are necessarily reductive, Reisman said, teachers must look to other sources to help give students a fuller picture of historical events — and it only takes one single document, juxtaposed against the textbook itself, to reveal the interpretive nature of history.

“Culture wars that fixate on history education reveal how hard it is for people to accept challenges to the stories they’ve told about themselves,” Reisman concluded. “But it also reveals that as a country, we have an impoverished understanding of the work of doing history.”

The Symposium’s Second Day

The symposium concluded on Saturday with two separate three-hour sessions. The first, “Monuments and Memory,” explored the ways in which public monuments — and the places and shapes in which they exist — shape memory and are themselves shaped by understandings of history. The second, “Me v. We,” explored the languages of rights, responsibilities, citizenship, inclusion, and exclusion in the Declaration of Independence and more broadly in early America. Penn GSE was represented in each session, with postdoctoral fellow Lightning Jay giving a talk in the first and Jonathan Zimmerman, the Judy and Howard Berkowitz Professor in Education — and member of the symposium's planning group — moderating the second.

The Meaning Behind the Monuments

Jay started by noting that his work focuses on translation — moving complicated and abstract ideas into a discussion space more accessible to students. That work begins with the question: where is history? Broadly, history is dictated by the shape of the land and how it impacts the way people live in it, just as it’s also dictated by the ways in which people shape the land they live in. Jay pointed to the fact that Philadelphia, the first gridded city in North America, wears its history proudly.

Some of that history is told through monuments, which Jay referred to as “a space where we tell the history to ourselves, a commentary that extends beyond place.” Which can be a challenge for teachers, because it — sometimes literally — carves a narrative into stone.

“Historians are constantly engaged with this question of, how do we know what we know?” said Jay. “How reliable is our information? We’re always confronting this incomplete historical record. And I want students to have access to that kind of thinking because that’s the way history is authentically created.”

Jay stressed the importance of getting students to think about history as less a defined, distant puzzle and more an important reflection of both our past and present — of convincing them they are stepping into a stream that impacts them every bit as much as they impact it.

To give an example, Jay talked about a curriculum he developed around Octavius Catto, a Philadelphia educator and civil rights activist who fought for desegregation in the city in the 1860s. For nearly 150 years after being gunned down in the street while on his way to vote, Catto was largely forgotten in Philadelphia and beyond. But in the 1990s and 2000s, a remembrance campaign sprung up and Catto — whose legacy had been so forgotten it took a broad civic project to even locate his gravesite — now has a beautiful grave marker that reads “The Forgotten Hero,” a mural, and a huge statue at City Hall.

“The city made an effort to indicate something about itself by indicating something about him,” said Jay. “And that triggered me to say there’s something here to teach.”

The School District of Philadelphia requested a curriculum be written about the creation of the monument and the change happening within the city, and Jay got to work. He focused on giving his students the texts and context to lead them to ask grounded questions and interpret the history for themselves.

He built four sets of document-based lessons. The first focused on the life of African Americans in Pennsylvania prior to 1860, to help students understand Catto’s lived experience. The second asked why riots in Philadelphia so frequently targeted African Americans, which itself led to the dissolution of the distinction between the city and the county and thus shaped modern Philadelphia. The third focused on the question of how Philadelphia’s streetcars became desegregated, giving students a chance to investigate Catto’s role and see if the comparisons to Martin Luther King, Jr., are appropriate. The fourth was a look into how and why Catto was murdered.

Those four lessons gave Jay’s students a much better understanding of the past, he said, but he felt they didn’t quite understand how it spoke to the present. So he pivoted and looked to Catto’s monument. He asked students about the representative language of the monument and challenged them to design a supplement to it — to engage with the conversation and figure out new ways to represent Catto’s story.

“This is a specific example of the way we can use monuments to trigger both textual and personal work,” Jay said. “I think there’s potential to use some of these instructional principles in a variety of circumstances.”

Wrapping Up

The success of the symposium — in all, providing two days of engaging, interesting discussion about the complexities of teaching American history in an increasingly polarized political environment — marked a strong start to America 250 at Penn.

“I think it’s important we give students and the public the tools they can use to create their own explanations of what happened in the Revolutionary era, rather than falling into narratives of good people and bad people, good events and bad events,” said Hart. “I hope we can build on these issues. This is an experiment, and we hope it is the beginning of something greater.”

For more information about America 250 at Penn, visit the website here.

Media Inquiries

Penn GSE Communications is here to help reporters connect with the education experts they need.