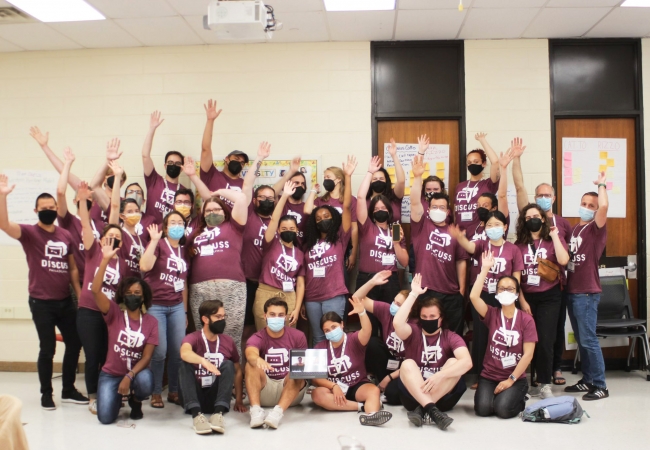

At DISCUSS Summer Institute, emerging teachers learn how to lead tough conversations about history and current events

For the second summer in a row, emerging teachers at Penn GSE spent a week learning how to lead tough conversations about history, civics, politics, and policy.

The DISCUSS Project, a collaboration between Penn GSE and Temple University, is a cohort-based program that tracks the development of pre-service and early-career teachers, starting with their first months in the classroom.

It’s not just a thought experiment: the teachers led in-person discussions for a room full of Philadelphia kids. The teachers prepared for the lesson by gathering a series of sources, such as news articles and historical documents. A sample topic might be, "Should you vote for third party candidates?" Students perused the documents and argued both sides of the issue, discovering many shades of gray along the way. Leading a discussion means encouraging students to interpret and evaluate history, rather than simply memorize it. It’s less didactic, more interactive.

After the discussion, the students provided their teachers with feedback in real time, and the teachers took a day to revise their lessons before re-presenting them on Friday.

"We manufactured a sense of urgency, so there was an authenticity to the work that is often missing in summer professional development," said Associate Professor Abby Reisman, who has taught in Penn GSE’s Teaching, Learning, and Leadership division since 2014.

The Penn GSE teachers in the summer program were graduate students in Reisman’s Social Studies Methods class. Thanks to funding from the James S. McDonnell Foundation, the teachers got paid to be part of the project. During the school year, they filmed a few of their discussions and took self-reflective notes about their performance. Education professionals then interviewed them about their videos, asking them to recall and reflect upon their instructional decisions.

A discussion-based pedagogy can work wonders in all subject areas, and much of the research has actually come from math classrooms. It turns out that when a teacher genuinely asks a student to contribute to the lesson, it increases the child’s motivation, engagement, and subject matter learning.

Yet, social studies poses a unique pedagogical challenge when it comes to discussion. Since the subject matter often overlaps with front-page politics, teachers can be hesitant to open up what might be a can of worms rather than a productive discussion. They realize that the subject of history — and how schools and districts teach it — has become a political football in recent years. But Reisman says that isn't necessarily new: "There has always been huge backlash against instruction that gets kids to think critically about history."

Another challenge of teaching social studies is that the curriculum often presents itself as a set of facts that kids need to memorize without critical reflection — a direct pipeline from book to brain. But Reisman says it's difficult for a teacher who sees history as a set of facts to lead a discussion: "A precondition of any discussion in history class is acknowledging that history is open to interpretation.”

That doesn't mean doing away with facts, but rather expanding the sources, viewpoints, and philosophies brought to the table.

"There will always be missing sources," Reisman says. "A teacher will always have their thumb on the scale in some way. But when teachers make this process transparent to students, they reveal the world of historical interpretation."