Discussing Nondiscussables

March 12, 2018

John D'Auria offers two strategies school leaders can use to turn conflict into open dialogue.

They are the things educators talk about in the hallway between periods or while monitoring the carpool lane. They are the complaints that linger at a weekend birthday party. They are what Roland S. Barth called the nondiscussable — the elephant in the room that no one wants to openly discuss except with trusted allies — and they can be the biggest obstacle to progress in school communities.

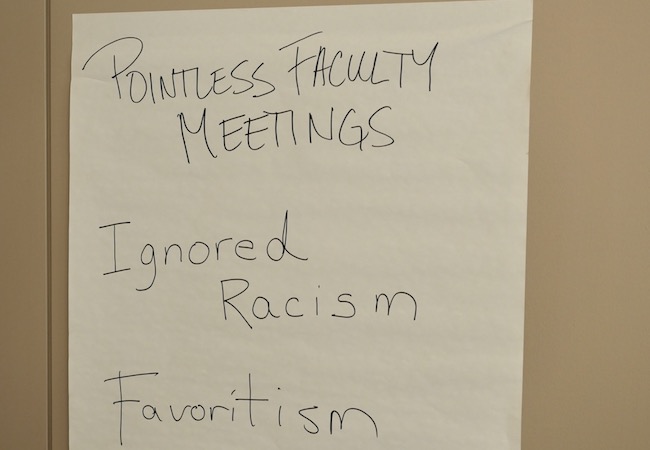

In leadership programs, I give aspiring principals sheets of blank newsprint and ask them to write down the significant issues they see going unaddressed in their schools. The underperforming teacher, they write. The veteran educator who regularly comes in late. The lack of trust in the principal. The dreary and ineffective faculty meetings. Race, and all its implications, especially on school discipline.

It’s not uncommon for these aspiring principals to ask for a second sheet of newsprint.

Educators rely on conversation and discussion as important pedagogical tools. So why are we so stuck when it comes to talking about a range of important issues that obviously grab our attention? There are many reasons, but one that often goes unmentioned is fear of conflict.

Conflict is viewed by many educators as something to avoid at all costs. Besides making us uncomfortable, raising opposing points of view or disagreeing with others can be seen as disrespectful and threatening. But silence and gossip don’t do any favors for individual teachers or the school culture. Barth suggested an important metric:

"The health of a school is inversely proportional to the number of nondiscussables: the fewer nondiscussables, the healthier the school; the more nondiscussables, the more pathology in the school culture."

Here are two strategies school leaders can use to discuss the nondisscussables and turn conflict into open dialogue.

Developing and assessing norms or public agreements

Think of norms or public agreements as the traffic signals that can guide a group through a discussion on a sensitive topic. Many schools have established norms, such as we will start and end our meetings on time. These are technical norms, and they are very helpful. But to discuss nondiscussables, we need to create adaptive norms. These are explicit guidance for addressing challenging group dynamics. For example:

- We will listen for the quiet voice, reach out to those who aren’t quick to speak up in groups.

- We will monitor personal air time. The group is large and our time is short.

- We will encourage the asking and raising of tough questions.

- We will be willing to engage in conflict and stay engaged to resolution.

When someone violates a norm—and someone, maybe even you, will violate a norm—make sure to offer a path back into the conversation. Address the violation, not the person who committed it.

Norms have little value if they are not regularly assessed. Experiment with regular, quick assessments. Here are two quick prompts that can provide timely and effective feedback:

- How well did I follow our norms? (On a scale of 1 to 5)

- How well did the group follow our norms? (1–5)

When group participants experience a sense that norms are not just words on a page but actual guidelines that need to be adhered to, safety increases, and people are more willing to talk about challenging issues.

Employing conversational protocols

Sometimes a subject is so loaded that members of your school community won’t feel comfortable offering their own opinion. At these times, conversational protocols can be a great asset. Here’s an example of how a discussion might play out using the Take a Stance Protocol, which I have found very useful.

Faculty members are grumbling about a new supervision and evaluation system, but few teachers are making specific complaints to their supervisors. The administration calls a meeting to directly address the concerns.

As the group assembles, faculty are randomly divided into two subgroups. Group 1 is given the task of working together to list on a sheet of newsprint all the ideas that they have been hearing about the new supervision and evaluation system that are positive or improvements over the old system. It is important to note that the directions are to share not their own thoughts but what they are hearing around campus.

Group 2 is given the task of naming all the ideas that they have been hearing that are critical of the new system. Again, the idea is not to directly ask for the group members’ thoughts but what they have been hearing. Within fifteen to twenty minutes, each group will produce a list of perspectives. Often, the nondiscussables are found within Group 2’s list. The protocol provides the anonymity and the opportunity for people to feel safe in raising their concerns. Once raised openly, the next step is to facilitate a discussion about one of the nondiscussables in a manner that ensures psychological safety and the airing of multiple perspectives.