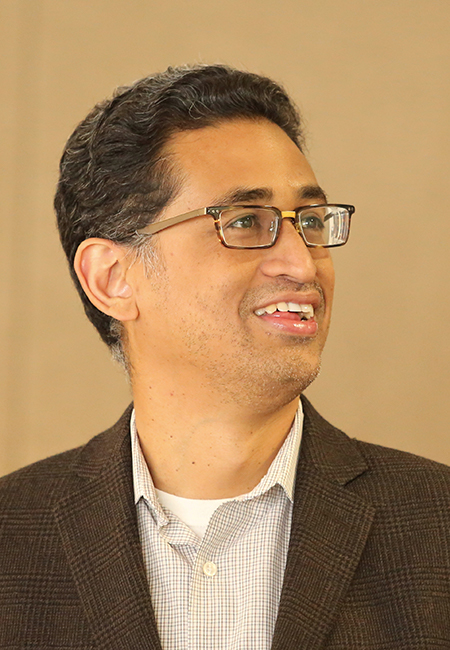

Fostering Civic Engagement: Two Penn GSE Professors Work to Close a Gap

interview by Juliana Rosati

What helps a child become an adult who votes? What can educators do to produce active citizens who voice their opinions to elected officials, volunteer for charities and community organizations, or even run for office? During the past three years, Penn GSE’s Professor Sigal Ben-Porath and Assistant Professor Rand Quinn have been studying civic engagement among students at two West Philadelphia high schools, working to understand how differences in school environments can affect students’ opportunities to develop as citizens. We sat down with Drs. Ben-Porath and Quinn to learn how their study, supported by the Gregory and EJ Milken Foundation, aims to inform teachers, researchers, and policymakers.

What prompted your study?

Ben-Porath: There has been a larger effort in education to try to understand some of the additional factors beyond academic achievement that should be considered when we assess school success and the ways that students are prepared for life after high school. One of these factors is civic engagement, meaning the capacity that students develop to be productive and contributing members of their communities and their society. It includes their sense of themselves as having something to contribute, as well as their trust in public institutions.

Quinn: There’s reason to believe that the civic engagement of young people has implications for their engagement in adulthood. In addition, there is a civic empowerment gap that many have written about. Young citizens from communities of color, low-income households, or immigrant backgrounds tend to be far less civically engaged and have far fewer civic opportunities than their counterparts who are white, middle- and upper-class, or native-born. Sigal and I wanted to study civic opportunities in two different school communities to try to understand the relationship between school context and civic engagement.

What kinds of civic opportunities were you looking at, and why is school an important place for students to encounter them?

Ben-Porath: School is the one institution that is really open to everyone and is the most longstanding in young people’s lives. Many studies show that it’s not primarily the content you learn—in a social studies or government class, for example—that influences your civic behavior. More important are the ways in which schools are engaging with students’ perspectives and preferences, as well as teaching them about boundaries and expectations through disciplinary practices. To what extent is the school recognizing the voices of students— for instance, by incorporating discussion time into class, or responding when students organize to start a club? How do rules allow students to learn about interacting with peers and authority?

“Teenagers are going to try to find out what kind of boundaries they can push and what kind of power they can exert.”

How did you conduct your research, and what were you looking for?

Quinn: Sigal and I worked with a team of Penn GSE doctoral students to study two West Philadelphia high schools. Though the schools are only about two miles from each other, they are very different. One is a neighborhood school that enrolls students who live nearby. The other is a charter school that exhibits elements of a “no-excuses” model, meaning there is a regimented form of behavior management. Some of its students have chosen to enroll from outside of the neighborhood. Our doctoral students observed spaces throughout the school—classrooms during core content classes, certainly, but also the hallways between periods, the cafeteria during breakfast and lunch, and areas used for after-school activities. We also interviewed and surveyed the high school students. We wanted to document various behaviors and assess the extent to which students felt that their voice mattered, or that they were able to have a say in discussions.

What have your findings shown so far, and what impact do you hope the study will have?

Ben-Porath: We are still in the process of analyzing our data, but we can say that we found some differences in civic engagement between the two schools, and we do believe that both school models can learn from each other. The ways in which teachers allocate their main resources in the classroom—their space, time, and attention—can have a significant effect on students’ civic engagement. This doesn’t require additional resources, just knowledge of particular practices. We have been developing a paper and toolkit for teachers to use in different school contexts to promote civic opportunities for students. We also want to look at broader policy implications for the non-academic assessment tools that schools are expected to develop. (See “Tips for the Classroom” below to learn more about Ben-Porath and Quinn’s tools for teachers.)

Quinn: There are some very practical, policy-relevant, actionable practices that school districts, particularly those that are under-resourced, can employ to broaden opportunities for students to engage civically. We also want to help researchers and others study civic engagement and participation in the classroom, so we developed a classroom observation tool that can be used to track the nature and tenor of a classroom in regard to these issues. It was published on www.civicyouth.org, the website of the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement at Tufts University.

Why do you believe this work is important?

Ben-Porath: Teenagers are going to try to find out what kind of boundaries they can push and what kind of power they can exert. It’s natural developmentally, especially in an institutional context. We need to understand what they are learning about whether their efforts make a difference, whether systems listen to them, what rules and expectations mean, and how to be resourceful.

Quinn: Researchers often focus on academic achievement as an important educational outcome, but civic engagement is also important. Just like closing or narrowing the academic achievement gap, reducing the civic engagement gap is ultimately beneficial to society.

Tips for the Classroom

Ben-Porath and Quinn offer these practical ideas for teachers of any subject who are hoping to introduce their students to civic engagement:

Let students speak. The way students learn to engage with issues and ideas in the classroom can become a model for how they engage in the community. Create opportunities for students to reflect on what they are learning and formulate their own opinions and views. This will help students foster a sense of themselves as valuable members of their society.

Be flexible. When a student brings up a personal experience that is relevant to your lesson, create space for him or her to share this with the class, either at the moment or at a later time. A key aspect of learning to be a civic actor is the ability to consider a topic and analyze it based on one’s own opinions and experiences. It’s OK to deviate slightly from your original lesson plan.

Rethink your room. Consider grouping desks together, or arranging them in a circle instead of rows, so that students will interact with each other in addition to you. Bring children of different abilities together. This can encourage a sense of a learning community. Civic engagement is not just about listening to one person and responding; it’s also about sharing and learning with peers.

These tips, written with doctoral student Jacquie L. Greiff, are adapted from The Educator’s Playbook, a monthly Penn GSE newsletter for K–12 educators. Visit www.gse.upenn.edu/news/subscribe to sign up.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2017 issue of The Penn GSE Magazine.