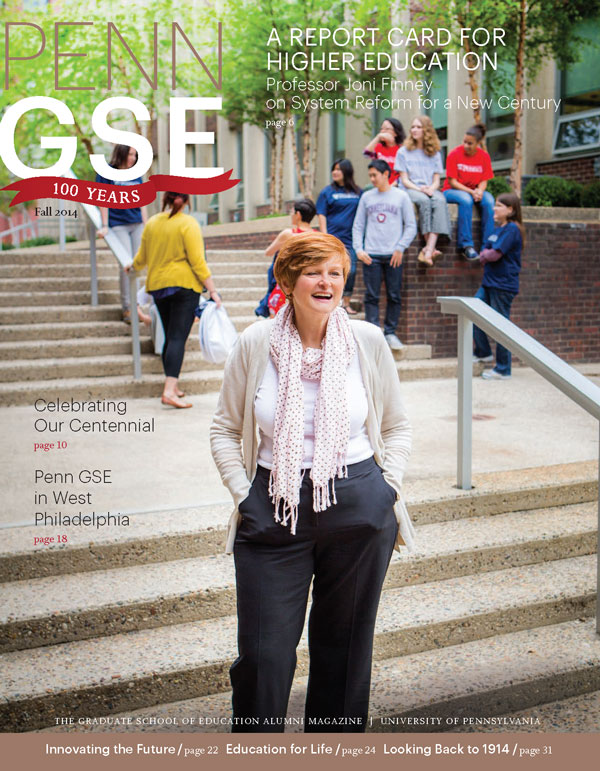

A Report Card for Higher Education: Professor Joni Finney on System Reform for a New Century

by Juliana Rosati

“We need to create pressure so that political leaders will address higher educatio

Students must make the grade through a host of challenges on the road to earning a college diploma. But who is grading higher education to ensure that students’ efforts and investments pay off, and that a college education is available to all who need one?

For the past fourteen years, Penn GSE Practice Professor Joni E. Finney has been turning up the heat on state leaders throughout the nation, pushing them to bring their attention to this question.

“I often say that states have the best public policy model for twentieth-century American higher education. The problem is, we’re in the twenty-first century,” says Finney, director of the Institute for Research on Higher Education at GSE. “States have not adapted to address the new realities of the workforce and our democracy.”

Any call for reform will face opposition, and Finney has encountered her share. Prior to her time at GSE, she prompted outrage and later acceptance on the part of governors and state legislators by pioneering the development of the nation’s first report card on higher education. At GSE, she joined forces with Professor Laura W. Perna, whose scholarship focuses on improving educational attainment, especially for students from underrepresented groups. The pair’s findings on higher education in five states triggered resistance by leaders unhappy to see their states’ failures make headlines. Looking to monitor a larger group of states, Finney has sparked controversy by investigating California’s long-admired public higher education system.

Finney speaks of these challenges with a calm determination and makes it clear that her approach is about building public support for change. “We need sophisticated leadership by state leaders and citizens who are willing to raise questions that might be uncomfortable for college and university administrators— raise the right questions, not attack,” she says. “You have to be a friend, but a critical friend.”

Measuring Up: A Challenge to Fifty States

As vice president of the National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education from 1997 to 2007, Finney broke new ground by developing and directing the first evaluation of state higher education performance, a biennial state-by-state report card called Measuring Up. Produced independently of government and of higher education, the report card sought to represent the public’s interest by evaluating higher education in each state, including public, private not-for-profit, and for-profit institutions. “The idea was to create competition that would encourage states to improve,” says Finney, who notes that states, rather than the federal government, shoulder the primary responsibility for policies that can put higher education within reach of their residents.

Using data from national sources, the report card gave each state letter grades in six key areas: preparation of students for college, participation (the extent to which citizens pursue education beyond high school), affordability, completion of certificates and degrees, the benefit of college-educated residents to the state economy and society, and the level of skill and knowledge of graduates.

Finney faced hostility when the report card first came out in 2000. “Some governors and other state leaders were outraged that they were being rated and held accountable for their work in education,” she recalls. “We were fortunate to have a high-level board of trustees made up of governors, legislators, and business leaders who surrounded and protected us. We needed that political firewall.” Over the years, Finney saw the concept gain acceptance and become a barometer. “Smart governors, legislators, and educators knew how to use it as leverage to get something done,” she says.

Across all six areas, the grades revealed the same thing: in Finney’s words, “Where you live matters.” The report cards proved that educational opportunity varies dramatically across the country, with disparities that the United States cannot afford if the country’s workforce is to remain competitive in a global economy.

Though internationally the United States remains dominant in research, an area that the report cards did not measure, the country has fallen behind many other nations in college enrollment and completion. In 2012, the United States ranked fourteenth internationally in the educational attainment of young adults.

“We’re moving into a knowledge economy, and more people than ever need some training beyond high school,” says Finney. “Higher education has come to function as the gateway to the American middle class, so we have to create more opportunities.”

Digging Deeper: GSE Collaboration Probes Five States

While the report cards pinpointed states’ strengths and weaknesses, they did not offer reasons for them. Upon joining the faculty of Penn GSE, Finney teamed up with Professor Laura W. Perna to delve into the histories of five states—Georgia, Illinois, Maryland, Texas, and Washington—for one of the first studies to explain how state public policies have influenced higher education performance.

Perna, now Higher Education Division chair, brought to the project a vast expertise in the forces that keep college diplomas out of the hands of students. Through numerous studies, her research has addressed how students make decisions about attending college, the impact of college counseling and state- mandated tests on college opportunity, the circumstances of working and minority students, and the role of financial aid in promoting college affordability.

According to Perna, state accountability in higher education is all the more urgent due to proven shortages of opportunity for students from minority groups and low-income families. “Educational attainment is an important ingredient for a democratic society,” says Perna, the founding Executive Director of the Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy (Penn AHEAD), a research center dedicated to fostering open, equitable, and democratic societies through higher education. “Our country has substantial gaps in attainment across groups. These gaps are deeply problematic not only for economic competitiveness, but also for social justice.”

Five Histories

Finney and Perna co-directed the five-state study beginning in 2009. They first sought a detailed picture of each state’s higher education policies and performance since the 1990s. Strategically chosen for their relevance to larger issues, the states all boast large populations but have different economies, types of higher education institutions, and report card grades.

Among other questions, Finney and Perna wanted to know why Georgia and Texas earned low marks for participation, each receiving a D- in 2008, and how Texas had improved in preparation from a C to a B. They wanted to know why all of the states, including Maryland, had earned F’s for affordability in 2008, and why Washington was a top performer for completion with an A-, but earned a D for participation. And they wanted to know why Illinois earned straight A’s in preparation, participation, and affordability in 2000 but saw steep declines by 2008.

In collaboration with the National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, Finney and Perna, along with a research team of graduate students and policy analysts, visited each state to interview governmental, institutional, and business leaders. The findings were released as state reports in 2011 and 2012, as a national report in February of this year, and in Perna and Finney’s coauthored 2014 volume, The Attainment Agenda.

Low participation in Georgia was traced, in part, to discontinuities between governors’ policies and a lack of need-based financial aid, all of which perpetuated disparities for black, Hispanic, and poor students. The report on Texas showed that, given finite fiscal resources, leaders’ ambitious plans to create new research universities may compromise their goals for increased participation. At the same time, it revealed that Texas is improving preparation through the design and evaluation of high school courses and tests.

The report on Maryland, a national leader in educational attainment, showed the state had made strides toward affordability by freezing tuition, stabilizing state appropriations, and linking tuition increases to family income, but the economic downturn had stalled many of these efforts. The Washington report identified a host of issues that contributed to relatively low numbers of bachelor’s degrees, including statewide leadership problems, failed efforts to restructure higher education governance, and skyrocketing tuition. The researchers found that the outstanding performance of Illinois declined as the state moved to a more decentralized structure for higher education oversight and failed to use fiscal resources strategically.

Finney and Perna have seen state leaders balk at the picture painted. “There was some defensiveness,” reports Finney. Prominent media coverage in all five states brought the news to residents, paving the way for the development of the more informed citizenry that Finney believes is necessary for higher education reform.

Common Lessons

With a detailed portrait of each state in hand, Finney and Perna looked for broad themes. “We wanted to step back and identify conclusions that cut across the five reports, with the goal of offering insights for other states,” says Perna.

All five states need to increase educational attainment in order to stay economically competitive, and to do so in a way that will be economically feasible for taxpayers, students, and families. Finney and Perna recommend that any state’s attempt to solve such issues should draw upon several key lessons.

First, each state’s specific context must be taken into account. “This seems obvious, but it’s amazing how policies sweep the country, and a policy idea from one governor is just planted in another state with little consideration of how well it will work,” says Finney.

Second, state officials must provide leadership for higher education, rather than assuming that individual institutions’ aspirations will together serve the public’s interest. “We need better checks and balances. At the end of World War II, we had oversight mechanisms in place that were strong enough to match the power of the colleges and universities, but we no longer do,” says Finney. Such oversight must involve a shared agenda with institution leaders, notes Perna. “We need a shared understanding that state policy leaders must steer institutions to achieve statewide goals for educational attainment and closing gaps,” she says.

Third, states must focus on policies addressing three categories—financial resources, academic preparation, and the needs of the population—in order to maximize the potential of higher education and level the playing field for students. States should integrate their management of appropriations for public institutions, tuition policies, and financial aid so that resources are used strategically. Academic requirements in high schools, two-year institutions, and four-year institutions must be linked so that students can progress without spending time in remedial courses or finding that their credits do not transfer. Institutions’ offerings, from work- force certificates to associate’s and baccalaureate degrees, should be tailored to the needs of the population and employers in the state. In addition, institutions should seek new ways to become more accessible to citizens, such as offering summer and evening courses and online programs.

Building Pressure: California and Beyond

Aiming to develop a group of at least fifteen states to monitor in depth on a regular basis, Finney has turned her sights to California, which boasts the world’s twelfth-largest economy and 14 percent of all undergraduates in the nation. She worked with students in her advanced public policy seminar at GSE to examine higher education performance in the Golden State.

Released in April, their report, “From Master Plan to Mediocrity: Higher Education Performance and Policy in California,” reveals that despite a long-envied public system, higher education in the state has failed since the 1990s to keep pace with economic and demographic changes. If the downward trend in degree attainment continues, it will result in severe shortfalls of educated workers and troubling economic consequences for both the state and the nation.

“Because of the outsized role that California plays in the nation’s economy and in educating the nation’s college students, you could say that the system is too big to fail,” says Finney.

The report prompted a public response from University of California President Janet Napolitano and California State University Chancellor Timothy White, who noted the strengths of California’s system and pointed to improvements that are already underway.

That kind of public accountability is what Finney believes will spark efforts for change. “We need to create pressure so that political leaders will address higher education as an important policy agenda,” she says. “We need courageous leaders to grab the bull by the horns and create long-term plans that will take us thirty to fifty years out and strengthen the enterprise of higher education both for the states, and for the country as a whole.”

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2014 issue of The Penn GSE Magazine.