Science, Coding, and Citizenship: Penn GSE’s Dr. Susan Yoon Brings App Inventor to Philadelphia Schools

by Juliana Rosati

Penn GSE Associate Professor Susan Yoon wants science to empower students—both to develop the skills their futures will require and to live as engaged citizens.

“Science content and processes are not just academic things,” she says. “I want students to be able to take what they learn and apply it in the world to do good and effect change.”

Through a variety of research projects, Dr. Yoon has developed tools, curricula, and teacher training to bring science to life for students in ways that improve learning and incorporate twenty-first-century skills.

In her latest project, she is developing a way to teach science and computer programming, or “coding,” simultaneously. Supported by the Gregory and EJ Milken Foundation, the Lori and Mark Fife Foundation, Penn’s University Research Foundation, and the National Science Foundation, the project could meet a need felt by schools across the country.

A Curriculum for Change

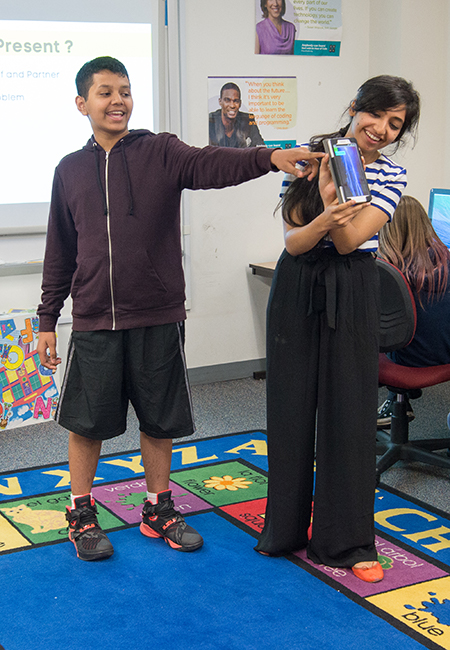

Aiming to put students in the role of change agents, Yoon’s project asks students to think of a science-related problem in their community and design a mobile application, or “app,” to provide a solution. Last spring, Yoon and two Penn GSE master’s students created and ran a pilot curriculum in a classroom at the K–8 Penn Alexander School in West Philadelphia, where GSE leads a University-wide partnership with the school. Students’ apps addressed nutrition, fitness, energy consumption, and recycling.

“We really want to impart to students that they can do a good thing for the world and give them the courage to take an active role in their communities,” says GSE student Jooeun Shim. She and her classmate Noora Noushad, both members of GSE’s M.S.Ed. in Learning Sciences and Technologies program, are working with Yoon as managers of the project.

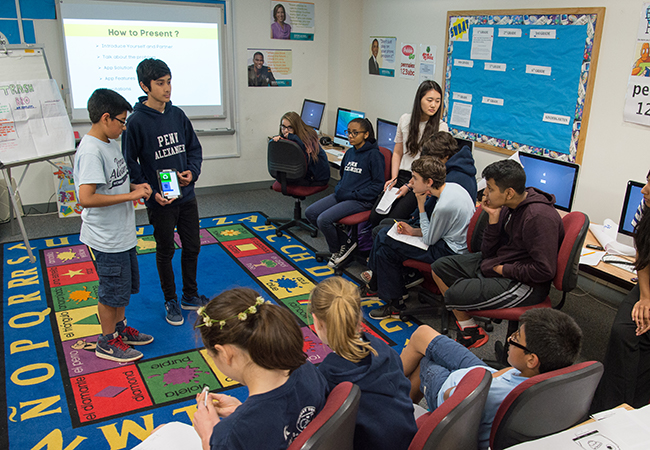

Working in groups, the Penn Alexander students developed apps for tablet devices using a visual coding language called MIT App Inventor. Visual coding uses colorful blocks that students assemble onscreen to create instructions for the computer. Because students don’t have to learn a programming language—a process known to dampen their interest—they can quickly focus on the larger coding concepts involved in building an app.

“It’s like putting a jigsaw puzzle together, and you get immediate feedback,” says Yoon. “You put together a sequence of blocks and then you look at your app and see if it’s doing what you asked it to do. If it isn’t working, you have to figure out why.”

Noushad and Shim took on the role of teachers for the pilot curriculum. “They achieved a nice balance of independent work followed by peer feedback,” says Penn Alexander teacher Peter Endriss, whose classroom was selected as the pilot site. Noushad and Shim also conducted research on the students’ learning, surveying the seventh graders periodically to discover which teaching approaches worked best.

“We really want to impart to students that they can do a good thing for the world and give them the courage to take an active role in their communities.”

By the end of twelve weeks, the nutrition app connected the school lunch menu to nutritional information so that users could make informed food choices. The fitness app provided workout and diet plans for achieving health goals. The energy app tracked the energy consumed by a user’s appliances to highlight the importance of conservation. The recycling app encouraged responsible waste disposal by showing how to recycle various items and what they would likely become.

“It was great to see the students show off the apps they had created,” says Endriss. “The apps weren’t just games or entertainment. They were meant to help others make some sort of change in their daily life.”

Noushad notes, “The curriculum sends the message that you don’t have to wait until graduation, or after college, to have an impact on the world—this is something you can start thinking about now.”

Partnering with Teachers

Across the United States, a movement toward teaching coding in schools has grown quickly in recent years. In an effort to foster complex thinking skills and prepare students for a future in which programming skills may be a necessity, New York City and San Francisco have announced plans to bring coding into every public school, and the Chicago Public Schools have made coding a graduation requirement. At the same time, many states and districts have adopted the Next Generation Science Standards, a new set of best practices in science education. The standards include an emphasis on skills in computing, engineering, mathematics, and scientific argumentation—aptitudes coding is thought to promote.

Yoon believes that the App Inventor curriculum can yield many benefits sought by schools, while helping students become socially responsible citizens. But she knows that such a curriculum cannot succeed widely without a plan for preparing teachers to use it.

“We know from research that technology integration for teachers has quite a steep learning curve,” says Yoon. “Teachers may not know how to use the technology to support their instructional goals, or they may not have the time or resources to use it effectively in the classroom.”

Since the Penn Alexander pilot, Yoon, Noushad, and Shim have been collaborating with The School District of Philadelphia to customize their curriculum to the district’s needs and make plans for training teachers. They aim to launch a professional development program in early 2017.

“We want the curriculum to be something any teacher can pick up and implement for their class or after-school program,” Yoon says. “There’s a ton of research on how teachers learn. They learn by examining their own practice, by testing things out, by being reflective, by working together in a professional learning community.”

Yoon has applied these principles to other projects that bring technology and best practices to science classrooms. As a partner in BioGraph, she collaborated with MIT’s Scheller Teacher Education Program to help teachers integrate coding and visual simulations into biology lessons. The project used a program called StarLogo Nova, which simulates complex scientific systems—like an ecosystem or human respiration.

“Complex systems are emphasized in the Next Generation Science Standards, but they are difficult to teach,” Yoon says. “With the StarLogo curriculum, students’ understanding of biology and systems typically increased threefold.”

As principal investigator of the ITEST- Nano project at Penn, Yoon collaborated with Penn Engineering to provide teacher professional development in nanotechnology and bioengineering.

The project trained seventy-six middle- and high-school science teachers in The School District of Philadelphia.

Like the App Inventor project, ITEST- Nano’s curriculum prompts students to think about scientific issues affecting their communities. For example, teachers ask students to make a decision about whether they would want a company that produces nanoparticles to move into their neighborhood given the environmental risks.

“Students come up with different responses to this problem and present them to the class,” says Yoon. “It makes learning authentic.”

Across all of her professional development work, Yoon keeps a focus on collaborating with teachers. “Teachers know their classroom best, they know their practice best, and they know what they can do best,” she says.

Working Together

From collaborating with Penn Engineering colleagues on ITEST-Nano to bringing the App Inventor project to The School District of Philadelphia, Yoon is most concerned with how people can collaborate to bring science to life. Teachers need professional learning communities; students benefit from peer feedback; and researchers need the perspectives of multiple organizations.

“What underpins all of these projects is the question, ‘How can people work together to build better science programs?’” she says.

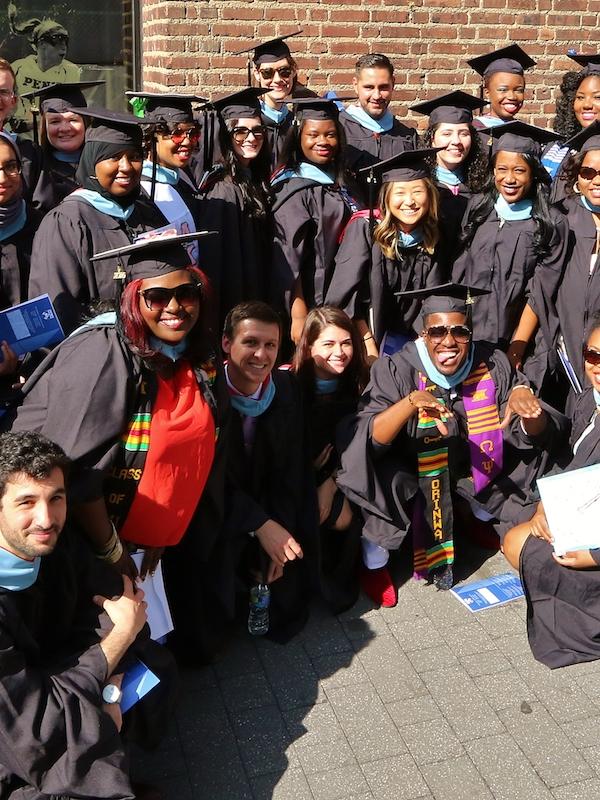

According to Noushad and Shim, the App Inventor project has already provided a compelling answer for two budding educators. Both approached Yoon voluntarily to work on the project and have discovered a professional mentor in their professor, as well as a research partner in each other.

“It’s been a great learning experience for us,” says Shim, who plans to pursue doctoral study. “Dr. Yoon has shown us how to think like a scholar and how to conduct research professionally.”

Adds Noushad, “I wanted the chance to apply what I had learned in Dr. Yoon’s class, but this became much more.

I’m now thinking about how we could bring a curriculum like ours into developing countries. Dr. Yoon has been a great mentor.”

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2016 issue of The Penn GSE Magazine.