Do We Have Too Many Teachers?

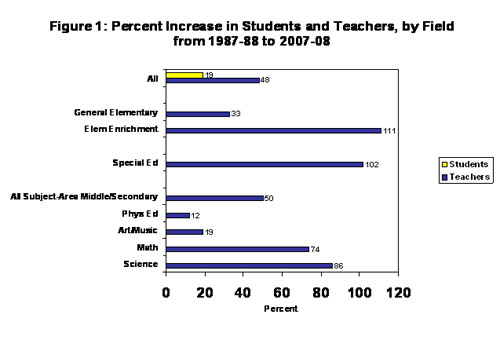

March 2, 2011 - Over the past 20 years, total student enrollment in American K-12 schools grew by 19 percent, but the teaching force increased at over 2.5 times that rate — about 48 percent.

Even with this dramatic increase in the teaching force, though, there is considerable anxiety in the U.S. about a “teaching crisis” – President Obama, for example, called for the preparation of 100,000 new math and science teachers in his state of the union address. So what’s going on? What’s the story behind the teaching force statistics?

Richard Ingersoll, a professor at Penn GSE and expert on the teacher workforce, is finding out. Taking a close look at the numbers, Ingersoll drew some surprising conclusions with implications for the profession. The first figure – the rise in student enrollment – is easily explained by the baby boomlet of the 1980s, but the second required considerably more analysis. How could the rate of increase for teachers outpace that for students so dramatically? Why the disproportionate expansion?

One hypothesis is nationwide efforts to reduce class size – smaller classes mean we need wore teachers. At the elementary level, class sizes have dropped about 20 percent in the past decades. And because elementary teachers represent such a large portion of the teaching force – almost one third – an increase there has done its part in contributing to the ballooning.

But Ingersoll’s research identified an even more significant factor: the growth of special education, linked to mandates in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. “During this period,” he explains, “special education alone has accounted for almost one fifth of the entire increase in the teaching force with the number of special ed teachers increasing by 102 percent. That compares to a 33 percent for general elementary education.”

Along with the ballooning of the teacher workforce overall have come large shifts at the middle and secondary levels, with the number of subject-area teachers increasing there by 50 percent. That growth has been concentrated in core academic subjects (especially math and science) and special education. “Interestingly,” Ingersoll notes, “the data also show that the fastest rate of increase in math and science teachers occurred during the 1990s, before the advent of the No Child Left Behind Act.”

Along with the ballooning of the teacher workforce overall have come large shifts at the middle and secondary levels, with the number of subject-area teachers increasing there by 50 percent. That growth has been concentrated in core academic subjects (especially math and science) and special education. “Interestingly,” Ingersoll notes, “the data also show that the fastest rate of increase in math and science teachers occurred during the 1990s, before the advent of the No Child Left Behind Act.”

Ingersoll speculates that other education policies – in the form of high school graduation requirements – have played a key role as well. “During this period, as states beefed up graduation requirements in math and science, the data show an increase in student enrollment in those subjects — by 69 percent and 60 percent, respectively,” he explains. “No doubt, this phenomenon has driven the large increase in teachers in those subjects.”

What does this trend mean for the profession? Particularly in budget-conscious times like these, the bottom-line implications are “sobering,” says Ingersoll, “given that teacher salaries are the largest item in school district budgets.”

For more analysis from Richard Ingersoll, click here.

Contact: Kat Stein, Exec. Director of Communications / katstein@gse.upenn.edu / (215) 898-9642