Getting to the Core of Project-Based Learning: Penn GSE Supports a National Network of Teachers

by Juliana Rosati

Design a public park. Conduct a mock trial. Write a letter to the editor. These are just a few examples of the tasks students might undertake if their teacher embraces the recent shift toward active and project-based learning. Such approaches put students at the center, asking them to plan and produce projects during class rather than simply receive information from a teacher. Research reveals that learning in this way has clear benefits to students—such as increased engagement, greater academic growth, and better preparedness for college.

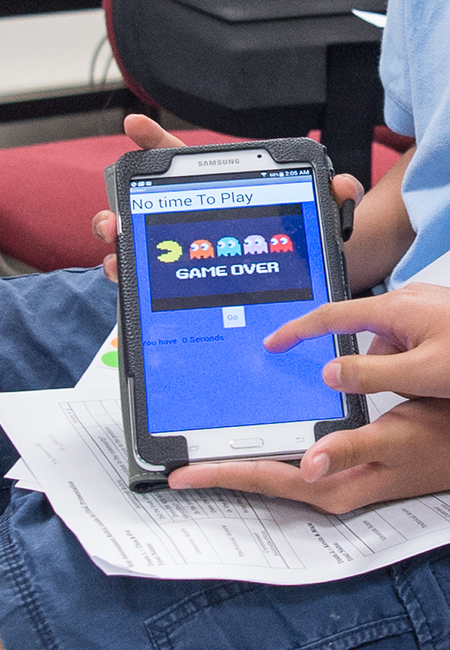

Yet project-based classrooms pose complex challenges for teachers. At any given moment, each student could be doing something different. One student might be making a drawing while another is building a model in three dimensions. One group might be struggling to assign roles to each member while another is looking for a good reference source. How can a teacher ensure that every student is learning academic content along with important skills such as taking initiative, working effectively in a group, and conducting research?

Penn GSE is taking the lead in helping educators across the country hone their skills in project-based instruction. Through a new certificate program and a related research project, the School is building a national network of teachers and leaders with the insight and experience to maximize active learning in their classrooms. This work is conducted in partnership with The School District of Philadelphia and two of its schools that have embraced project-based learning, The Workshop School (and its nonprofit affiliate Project Based Learning Inc.) and Science Leadership Academy schools (and its nonprofit affiliate Inquiry Schools), as well as the national organization EL Education.

Penn GSE Dean Pam Grossman views this investment in educators as critical to the success of innovation in education. “The future of education depends upon an investment in the very human resource of teachers and leaders,” she says. “The most innovative idea or technology can’t transform teaching and learning without the presence of inspired, knowledgeable, and skilled educators.”

Matthew Riggan, GR’05, cofounder of The Workshop School, a project-based school in Philadelphia, sees the need firsthand. “There is a human capital problem in project-based learning,” says Dr. Riggan, a member of the certificate program’s advisory team. “Schools of education traditionally do not prepare people to teach in this way. Penn GSE’s commitment to addressing this issue is very important, both symbolically and practically.”

A Vision of Ambitious Teaching

Designed for experienced educators who have already brought active learning to their classrooms, Penn GSE’s Project-Based Learning Certificate Program launched in August 2018. The inaugural class is made up of forty-one teachers and five educational leaders. Participants represent public and independent K–12 schools in seven states and the District of Columbia, and teachers in the group boast an average of eleven and a half years of classroom experience. Rather than provide a specific curriculum for educators to use, the thirteen-month program emphasizes an often-neglected topic: the actions and decisions of effective project-based teachers.

“You could walk into two separate classrooms with two different teachers leading the exact same project and see very different things going on,” says Penn GSE Lecturer Zachary Herrmann, director of the Project-Based Learning Certificate Program. “Just having a high-quality project isn’t enough. What is the teacher doing in the moment to bring that project to life?”

That practical focus is rooted in the research of Dean Grossman, who has studied the essential, or core, practices of effective teachers for years. While a professor at Stanford she developed a tool for observing the instruction of English teachers and helping them to improve. Her most recent book, Teaching Core Practices in Teacher Education (Harvard Education Press, 2018), advocates for components of effective teaching that have been identified through research.

When it comes to project-based learning, Dr. Grossman believes it is critical to focus on instruction. Project-based learning was attempted unsuccessfully in the 1960s with a “teacher-proof” curriculum that was thought to reach students no matter what the teacher did to implement it. “That whole notion is problematic,” says Grossman. “Study after study has shown that you can’t teacher-proof a curriculum. A curriculum is always filtered through a teacher’s knowledge, skills, and beliefs.”

Because a project-based approach asks students to take responsibility for their own learning, the teacher’s role is no longer that of a lecturer but rather a facilitator and coach. To help prepare teachers for this challenge, Grossman co-led a research project with Penn GSE Senior Fellow Christopher Pupik Dean, GED’09, GR’12, director of the Independent School Teaching Residency program.

The researchers on Grossman and Pupik Dean’s team surveyed project-based teaching experts—university researchers, teachers, and leaders of educational organizations—and observed the classrooms of successful project-based teachers. “We collected a lot of video of the teachers and analyzed it to try to understand what it was that they were doing that created effective learning environments,” says Pupik Dean. The result was a set of core practices for project-based teachers—the foundation of the new certificate program, which strives to meet an emerging need across the nation.

“Anyone who works in education will tell you that implementing ambitious, student-centered instruction, such as high-quality project-based learning, is the right thing to do,” says Penn GSE Research Assistant Professor Sarah Schneider Kavanagh, who is conducting a study on the certificate program. “However, as schools and districts begin to realize how difficult it is to do this kind of instruction well, one of the dangers is that they will say it doesn’t work. And it won’t work if they don’t support teachers.”

Grossman expresses great confidence that the “dream team” of Drs. Herrmann, Pupik Dean, and Kavanagh is equal to the challenge at hand. “Zachary is an incredible project leader with expertise in leadership and cooperative learning, as well as a background as an award-winning math teacher. Chris did the original research, has run Penn GSE’s independent school teacher education programs, and is an amazing educator. Sarah is a remarkable researcher who has focused for years on core practices and brings deep expertise in practice-based teacher development. I feel like we just could not have a better team,” she says.

Opening the Classroom Door

Weighing the pros and cons of disposable drinking straws, writing a poem, and planning a “desert survival” strategy are just some of the projects that participants took part in when they convened on campus for a week-long Summer Institute in August to kick off their thirteen months in the Project-Based Learning Certificate Program.

“If we expect our teachers to create rich and powerful learning experiences for their students, we need to create rich and powerful learning experiences for teachers,” says Herrmann. The educators not only participated in the kinds of projects they might assign to students, but also worked together to improve the projects and try out new teaching strategies.

At the heart of the institute and the program is the set of core practices of effective project-based teachers identified in Grossman and Pupik Dean’s study. These include encouraging students to make their own choices, collaborate with their classmates, reflect upon and revise their own work, give and receive feedback, engage in higher-order thinking, build personal connections to their work, and make a contribution to the world, all while they learn the content and practices of academic subjects.

Rather than prescribe a specific course of action, the practices serve as a framework that teachers can apply as they make long-term and short-term decisions about their course content and what kind of guidance to offer their students across a variety of situations. For instance, students may be more likely to feel personally connected to a project and see it as contributing to the world if the teacher asks them to solve a real problem in their community. If students are struggling with a project, subtle prompts and purposeful questions from the teacher may help them to get back on track while still encouraging them to make their own choices.

“We’re helping teachers develop their discretion,” says Herrmann. “We want to build our teachers’ capacity to make thoughtful and effective in-the-moment decisions that support their students.”

Morning sessions of the institute, led by Herrmann, brought all forty-six participants together to consider the core practices through group work punctuated by periods of individual reflection. In the afternoons, participants separated into six teams based upon the subject they teach. Each team worked with a facilitator to role-play and brainstorm practical aspects of implementing the practices.

“There is a human capital problem in project-based learning. Schools of education traditionally do not prepare people to teach in this way. Penn GSE’s commitment to addressing this issue is very important, both symbolically and practically.”

“As a teacher, you might not know what’s going on in the classroom across the hall, much less the one up two floors or across town,” says Meg Riordan, director of external research at EL Education and a member of the certificate program’s advisory team. As a contributor to the program’s design, Dr. Riordan took part in a year-long planning process involving individuals from over a dozen educational organizations in nine states. The outcome of that process, she says, is a structure that aims to open the classroom door so that teachers can learn from one another. “This program and the network it engenders give teachers a chance to make transparent some of the choices they are making behind the scenes that have an impact on students,” Riordan says. “You can report back to your team and say, ‘I experimented with something, and here’s how my students responded, and here’s the work they produced.’”

On the ground at their respective schools, the certificate program’s participants have been immersed in an academic year of putting their knowledge to work in their classrooms while continuing the Penn GSE program in a virtual format, regularly conferring with their facilitators and submitting videos of their teaching to an online platform so that their classmates can provide feedback.

Running parallel to the certificate program, a research project led by Kavanagh is gathering insights on the program’s impact. Prior to the program’s start, Kavanagh and a research team collected data on approximately half of the participants, including videos of their teaching and work that their students produced. The researchers will continue collecting such data, with the aim of identifying changes in the teachers’ practice and their students’ learning.

“We can reliably watch video of a teacher’s practice and determine whether or not that teacher is doing a lot or a little to support goals such as collaboration,” says Kavanagh. “As we watch videos of teachers over time, we will see the extent to which their skills in project-based instruction are growing.”

Pupik Dean adds, “We have built-in proof of concept. We’ll be able to demonstrate whether the program is effective or not from the research.” The results will point the way to enhancements of the certificate program as well as Penn GSE’s longstanding master’s programs in teacher education, all of which are now part of the School’s recently launched Collaboratory for Teacher Education at Penn GSE. The Collaboratory has expanded Penn GSE’s offerings for teachers and aims to evolve its programs continually on the basis of research.

Creating a National Network

At the Summer Institute in August, participants expressed appreciation for their time together and what they could accomplish in the months ahead.

“This year is going to be an exciting opportunity to build really substantial connections with the teachers,” said Melissa Viola-Askey, the facilitator for the U.S. History team and a social studies specialist at the Prince William County Public Schools in Manassas, Virginia.

STEM team facilitator Alissa Fong, an instructional coach at Stanford Graduate School of Education and a former math teacher, said, “Often when teachers are evaluated at their schools, the feedback is not really actionable. In this program, teachers can say, ‘Here’s something I want to practice, and I know I’ll be successful when I see a certain result, and my facilitator will help me with challenges that arise.’”

Participant Marcelina McCool, a world language instructor at Philadelphia Military Academy, described the program as a “dream come true” and praised the ways in which it exemplifies a student-centered approach. “As participants, we are the makers and doers of the program, not just learners,” she said. “It provides a safe environment to share our strengths and weaknesses and receive feedback from faculty and educators who are so passionate.” During the week, McCool came up with an idea for a new unit that would ask her students to argue for or against the concept of sanctuary cities by conducting research and writing a letter to local leaders.

“This program has the potential to create a pipeline of educators who are able to think critically about what it means to teach in a modern world, and what it means to create classrooms that are more authentic and student-centered.”

Stephanie Manis, a math teacher at Albert Einstein Academies in San Diego, California, was drawn to the program because of her positive experience in a professional development program that Dean Grossman led as a faculty member at Stanford University. At the Summer Institute, Manis role-played classroom situations with her team and set a goal of teaching her students the skills of revision and reflection. “I realized that just producing a project only takes students halfway,” she said. “They also need to reflect on their work and revise it, so that by the end they have a collection of knowledge.”

Rachel Zulick, a science teacher at Northern High School in Durham, North Carolina, appreciated the program’s focus on the core practices of project-based teaching. “That gave me a very clear direction for project-based learning that I haven’t come across before,” she said. “Now I can identify which of the activities in my classroom have been true project-based learning, and I have the knowledge to transform the ones that weren’t,” she said.

Samuel Reed III, a humanities teacher at The U School in Philadelphia, valued the challenge of examining his teaching practice. “The program is pushing me to think more deeply about how to engage students, convey disciplinary content, and ensure equitable collaboration in groups,” he said. He looked forward to sharing his knowledge with colleagues at his school and beyond. “I hope we can become cheerleaders for project-based learning and encourage others to practice it well,” he said.

After months of bringing new approaches to their classrooms and conferring with their teams, participants will conclude their time in the certificate program by returning to Penn GSE for a second Summer Institute. At the same time, a new group of educators will arrive on campus to begin the program. By building connections that are meant to last and enrolling a new cohort each year, Penn GSE aims to create a network of teachers and leaders who can meet the nationwide need for effective project-based learning.

“This program has the potential to create a pipeline of educators who are able to think critically about what it means to teach in a modern world, and what it means to create classrooms that are more authentic and student-centered,” says Chris Lehmann, a member of the program’s advisory team and founding principal of Philadelphia’s progressive, nationally recognized Science Leadership Academy.

For Dean Grossman, this kind of investment in teachers exemplifies a broader call to action. “We need to keep teachers at the center of the drive to improve education,” she says. “Let’s recruit some of the most innovative people in our society to teach. Then let’s support them and invest in their development—because the future of education depends upon them.”

Advancing Active Learning

While Penn GSE’s Project-Based Learning Certificate Program focuses on honing K–12 teachers’ skills in instruction rather than providing them with a specific curriculum to bring to the classroom, Penn GSE faculty have created curricula that advance active and project-based learning in a variety of subjects. Here are a few examples:

Making Electronic Textiles: Students design and create items such as stuffed animals, wristbands, hats, and laptop sleeves and embed them with electronic components like LED lights and sensors when taking part in a unit on electronic textiles developed by Penn GSE’s Dr. Yasmin Kafai, Lori and Michael Milken President’s Distinguished Professor. Released across the country as part of the widely adopted Exploring Computer Science curriculum, the unit aims to foster creativity and community while students learn about coding and circuitry.

Effecting Change Through Apps: Students think of a science-related problem in their community and design a mobile application to provide a solution when participating in a curriculum created by Penn GSE Professor Susan Yoon. Using a visual programming language called MIT App Inventor, students build apps that address issues such as nutrition, fitness, energy consumption, and recycling by encouraging responsible habits in their users. The curriculum seeks to teach science, coding, and good citizenship simultaneously.

Reading Like a Historian: Rather than memorizing historical facts, students work together to evaluate the reliability of historical documents and learn to make claims backed by evidence through the award-winning Reading Like a Historian curriculum that Penn GSE Assistant Professor Abby Reisman helped develop. The curriculum focuses on engaging students in the process of inquiry that historians use when evaluating the multiple perspectives presented in historical texts.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2018 issue of The Penn GSE Magazine.