Creating a World of Opportunity: Penn GSE Partners for Global Impact

by Juliana Rosati

Can a model for improving schools in one country be adapted to propel nationwide reform in another? How can a newly independent nation build a brand-new research university? How can preschool be strengthened on a national scale? Through an array of international partnerships and projects, Penn GSE is tackling these and other formidable questions to forge new paths and set new precedents for meaningful change in education.

“Penn GSE is deeply committed to approaching education from a global perspective,” says Penn GSE Dean Pam Grossman. “The School maintains a stellar international student body, provides a range of international learning opportunities for our students, and undertakes groundbreaking research and practice around the world.”

According to Penn GSE Senior Fellow Alan Ruby, founding director of the School’s Global Engagement Office (GEO), a global perspective is not an option but a necessity in education. “As educators and leaders, most of our students are going to participate in globally connected economies, whether in the United States or abroad,” says Ruby.

With international students from forty-four countries comprising 23 percent of the student body, Penn GSE represents a global community. Various degree programs, including the International Educational Development Program (see “Working on the Ground,” below), prepare students to shape education in international and multicultural settings. Across the School, students also participate in and learn from the research and practice that more than 70 percent of faculty are undertaking internationally. Encompassing a wide network of partnerships and collaborative scholarship, this work is the result of long-term effort. “Faculty including Drs. Nancy Hornberger, Dan Wagner, and Kathy Hall built the foundation of Penn GSE’s global footprint over the course of more than three decades in settings as diverse as China, France, India, Morocco, New Zealand, Panama, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and South America,” says Ruby.

According to Ruby, global work by faculty emphasizes transparency, mutual benefit, and respect for difference. Transparency ensures that the work will contribute to the field of education at large, not just a single institution or government. “We want the results of our research and practice to be publicly available for review and critique,” says Ruby. A focus on mutual benefit means cultivating a two-way exchange with international partners. “We should expect to learn as much as we teach,” says Ruby. “Similarly, we should respect difference—sometimes challenge and question it, but understand that someone holds a point of view because it matters fundamentally to them.”

In locations around the globe, Penn GSE faculty are engaging in work with the potential to transform early-childhood, K–12, and higher education in a variety of contexts. The stories below offer some highlights of this work.

AFRICA: Improving Early Childhood Education and Mapping Political Change

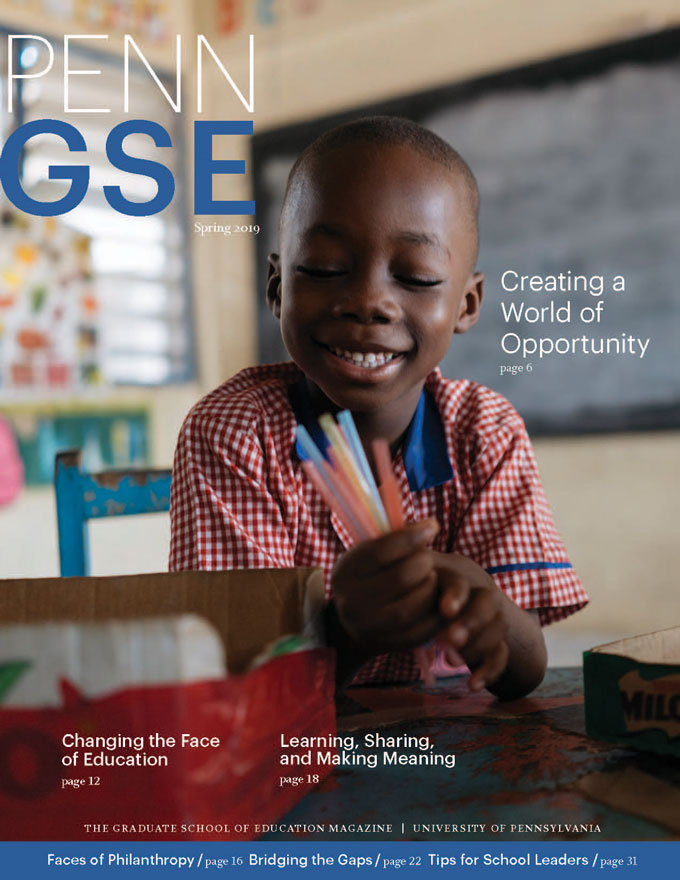

Considered a global leader in early childhood education, Ghana offers two years of public schooling, known as kindergarten, prior to first grade. Yet the quality of instruction in kindergarten classrooms has hampered schools’ potential to prepare children for primary school. When Ghana’s Ministry of Education and the nonprofit organization Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) sought to better implement a forward-thinking curriculum for the early years, they engaged Penn GSE Assistant Professor Sharon Wolf, C’06, to co-lead a large-scale training effort.

“A review led by the government concluded that many kindergarten teachers within the school system were trained to be generalist teachers and not prepared to focus specifically on kindergarten,” says Bridget Gyamfi, senior policy and implementation manager at IPA.

Dr. Wolf collaborated to create a five-day training program and deliver it to approximately 320 teachers at 160 schools in the urban region of Greater Accra, working with colleagues from Penn and New York University, Ghana’s National Nursery Teacher Training Center, and the nonprofit organization Sabre Education. The training, which benefited 2,650 students, encouraged teachers to make children active participants in the classroom. “In Ghana, and a lot of developing countries, the teacher typically leads the instruction and the children are mostly passive listeners,” explains Wolf. “We know this is not really how anyone learns best, but younger children especially need to be manipulating materials and participating in activities.”

The training also aimed to reduce corporal punishment, which is widely used in Ghana. “Often teachers don’t have other tools,” Wolf says. “A big part of the training focused on positive behavior management strategies.” Such strategies included developing a set of classroom rules that everyone agrees to follow.

“Increasing access to high-quality early education can really change children’s trajectories.”

The training was evaluated over a three-year period. The outcomes of surveys, classroom observations, and assessments with children set forth in scholarly articles by Wolf and her colleagues bode well for the possibility of training teachers on a larger scale. Quality of instruction, children’s school readiness, and teacher retention all improved measurably. The government has incorporated much of the training into its new national framework for early childhood teachers, and Gyamfi and her colleagues are considering how the practices can be spread to more teachers. “We want to understand how to apply the training in rural settings so that we can think of scaling it up more broadly,” she says.

Wolf, a Jacobs Foundation Research Fellow for 2018–2020 and a recipient of the Early Career Award from the Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness, aims to address a worldwide need. “About 89 percent of the young children in the world live in lower-income countries,” she says. “That’s a huge percentage of our future global population. Increasing access to high-quality early education can really change children’s trajectories.”

Penn GSE Assistant Professor Krystal Strong’s work in Africa carries international implications in another area—the role of education in political change. Imagine trying to study without electricity or teach without receiving a regular paycheck. At college campuses in many African countries, such problems rooted in infrastructural and governmental shortcomings prompt demonstrations, boycotts, and strikes by students and staff. With funding from a Small Grant from the Spencer Foundation, Dr. Strong has compiled a map that documents more than one thousand unique protest activities in higher education throughout Africa. She views these events as part of a larger phenomenon.

“There has been a sharp increase in movements for social change around the world over the past decade,” she says. Strong sees the disruption in Africa as resulting from a continent-wide tension between an old guard of aging political leaders and a total population that is the world’s youngest, with roughly 70 percent reported to be under the age of thirty. A proliferation of leadership training programs aimed at African youth is also a byproduct of this tension, Strong suspects. Through another project she is documenting global leadership academies developed during the past decade for young Africans. “These programs suggest that we can educate a new class of leadership into existence,” Strong says. “I’m very curious about what these programs intend to do, what the participants expect, and what the outcomes are.”

An anthropologist by training, Strong is writing a book about the nexus of education and political change in Nigeria. Through her work she aims to increase Africa’s presence in discussions of the larger educational and political landscape. “These are really interesting processes that should be a part of our research and understanding of similar dynamics around the world,” she says.

Working on the Ground

Penn GSE’s International Educational Development Program (IEDP) has developed close relationships with an extensive list of leading international development agencies. These afford Penn GSE students opportunities for internships that are unique worldwide and provide high-impact, on-the-ground experience. “IEDP’s international internship program has become recognized globally as providing exceptionally well-trained students for improving education in low-income countries,” says Daniel A. Wagner, IEDP director, professor, and UNESCO Chair in Learning and Literacy.

LATIN AMERICA: Creating Sustainable School and Professional Development

Penn GSE’s involvement in Latin America includes a new master’s program in literacy, thought to be the first in Mexico, and an educational leadership network touching Chile, Uruguay, and Argentina (see “Advancing Literacy and Leadership,” below). In Nicaragua, a ten-year partnership known as Semillas Digitales (“Digital Seeds”) has yielded improvement across twenty schools in coffee-growing communities—and produced a model that can be implemented at a larger scale in and beyond Nicaragua.

A decade ago, Duilio Baltodano, W’70, president of CISA Agro, part of the Mercon Coffee Group, sought a way to improve education in the primary school his family built at their coffee farm in the mountains of Nicaragua. He was gravitating towards a plan to introduce laptops in schools when Penn GSE Professor of Practice Sharon Ravitch, GR’00, learned of his plans. Noting that new technology would not be successful without an investment in professional development and broader school reform, Dr. Ravitch recommended that Baltodano consider a teacher-focused approach to create lasting change across the curriculum while also introducing technology.

“I suggested a more comprehensive, sustainable reform model where teachers have professional development— and then ultimately can become teacher mentors for the next school, and so on,” Ravitch says. Impressed with this vision, Baltodano initially provided funding for Ravitch and a team to work with seven of Mercon’s schools over a three-year period.

“By promoting a different methodology, we find that teachers within the system can do wonders.”

“We saw that this idea could be very transforming because the method of education in Nicaragua is very traditional,” says Baltodano, who founded the Seeds for Progress Foundation with his brother J. Antonio. The foundation supports Mercon’s corporate social responsibility programs by implementing Digital Seeds in Nicaragua and other coffee-producing countries.

Ravitch and her team took a “participatory” approach to develop the Digital Seeds model, meaning they engaged teachers as active collaborators to determine their knowledge, resources, and needs, developing solutions to challenges together. “I’m not an expert on what those teachers know and need—they are,” explains Ravitch, who previously used participatory methods to help teachers and educational leaders in Haiti reconstruct their schools after natural disasters. “Teachers were very much critiquing the curriculum, telling us what worked and what didn’t,” she says. The Digital Seeds model similarly places students in an active role in the classroom, departing from the schools’ previous reliance on traditional lecture-format instruction. To ensure that the approach would be relevant to the cultures and regional norms of each school and community, Ravitch and her team customized the model to each site.

Evaluations of the program reveal student improvement in areas including attendance, grades, reading, writing, math, critical thinking, and civic and moral development, as well as teacher progress in the knowledge, skills, and capabilities to implement the curriculum. Given the results after three years, Baltodano provided support to expand Digital Seeds across all schools supported by Mercon through the Seeds for Progress Foundation. A process of monitoring, evaluation, and follow-up ensures that the program has a positive and ongoing impact.

“Having the support of Sharon Ravitch and Penn GSE has been extraordinary from day one,” says Baltodano. “Their passion and commitment to the program, and more importantly, to the education of the children in the coffee communities, is shown in the growth and success of Digital Seeds.”

That success has been the result of a long-term partnership. Ravitch expresses gratitude for the Baltodanos’ commitment to supporting rigorous methods and lasting change over quick results. “The fact that they were so patient for a number of years while we built this program is tremendous and rare,” she says.

Because Ravitch and her team successfully replicated and customized the Digital Seeds model across schools, the program holds significant potential to be implemented on a larger scale. Baltodano, who recently introduced Digital Seeds in Guatemala, envisions bringing the program to more communities in Nicaragua, in collaboration with the Ministry of Education, and exploring how it can take root in other countries that are part of Mercon’s global reach. “This project deals with a great need in the world, which is improving education where the system is not capable of providing opportunity for the people,” he says. “By promoting a different methodology, we find that teachers within the system can do wonders.”

Advancing Literacy and Leadership

A new master’s program in literacy, thought to be the first in Mexico, has resulted from a collaboration with the University of Guadalajara led at Penn GSE by Professor H. Gerald Campano. In Chile, over 1,500 educators have completed a joint certificate program in educational leadership offered by Penn GSE and Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. Penn GSE Senior Fellow Michael C. Johanek leads the School’s work with that program and a related school leadership network based at Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, the Catholic University of Uruguay, and the Catholic University of Cordoba in Argentina.

ASIA: Transforming Higher Education Nationally

The efforts of Penn GSE faculty have shaped a university meant to set a new standard in another nation—the Republic of Kazakhstan.

Ten years ago when the Republic of Kazakhstan was preparing to establish Nazarbayev University (NU), the nation’s first research-intensive English-language university, officials looked to academic leaders and scholars at Penn for support, setting the stage for an enduring partnership.

“Building a new university from scratch is not for the faint of heart,” says NU Provost Ilesanmi Adesida. “It’s a post-Soviet country, so lots of processes and policies have to be established, especially of academic freedom, academic integrity, and university autonomy.”

“Our main goal is to produce young people who can become leaders in their fields and compete anywhere in the world.”

Former Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbayev, who took office shortly before the country declared its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, conceived of NU as a world-class research institution that would spur national economic development. Around the time of the university’s launch in 2010, a Kazakh team traveled to Penn for a weeklong course in administration and governance that helped shape the new university’s charter and board of trustees.

As the university faces the challenge of moving beyond Soviet-era norms in higher education and a curriculum largely dictated by the Ministry of Education, Penn GSE faculty provide perspective and advice. NU, which has been granted a significant amount of independence from the Ministry, is meant to set a new precedent for autonomy and excellence. “We want to lead the way for other institutions, not only in the country, but also in Central Asia,” says Dr. Adesida.

As other institutions in Kazakhstan follow suit in achieving greater autonomy, Penn GSE faculty are working with a research team from NU to track the process. “Some leaders are very excited about the possibility of having greater freedom to set a strategic direction for their institutions,” says Professor Matthew Hartley, who has worked closely with Ruby in Kazakhstan. “Others feel this is a brave new world in which they aren’t yet comfortable.”

Penn GSE faculty also mentor leaders, faculty, and doctoral students at NU’s graduate school of education, helping the school grow and become self-sustaining over time. “We’ve worked with the university to develop the school from an empty building,” says Penn GSE Senior Fellow Peter Eckel. “We help them think about establishing their curriculum, faculty, research capacity, and institutional strategy and policies.”

Having produced 2,721 graduates so far, NU represents an important part of Kazakhstan’s future. “We want to contribute through research to an innovation ecosystem within the country and in Central Asia. And our main goal is to produce young people who can become leaders in their fields and compete anywhere in the world,” says Adesida.

Improving Digital Literacy

Last fall, Penn GSE’s Virtual Online Teaching Certificate Program partnered with the Aditya Birla Education Academy to improve how teachers in India use technology. “We will help teachers develop their digital literacy so they can help their students cultivate twenty-first-century skills,” says VOLT Program Director Betty Chandy.

Looking Ahead

Penn GSE’s international impact helps to realize the global aims of the University, according to Dr. Ezekiel J. Emanuel, Penn’s vice provost for global initiatives.

“GSE’s work abroad not only illustrates Penn’s commitment to deliberate and thoughtful global engagement, but also exemplifies the University’s longstanding manner of unifying theory and practice,” he says. “To meaningfully understand and better the world, we have to be out there learning from the challenges and opportunities it presents.”

As the School shapes a strategy for the next chapter of its global engagement, the Penn GSE Global Engagement Office has established an advisory committee of faculty, staff, and students to explore new opportunities. And last fall Dean Pam Grossman lectured on the future of education in Norway and Singapore and met with government leaders and members of the Penn GSE community in Dubai and Abu Dhabi.

“On an international scale, education holds the potential to reduce poverty and disease, foster peace and equality, and create sustainable economic development,” says Grossman. “In our interconnected and diverse world, Penn GSE’s commitment to the global education community will only increase in importance and impact.”

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2019 issue of The Penn GSE Magazine.