Creating Opportunity Through Education: Penn GSE Alumni Lead the Way

by Juliana Rosati

Education has a unique power to open doors throughout life—to intellectual exploration, successful employment, informed citizenship, and more. But far too often, devastating obstacles stand in the way of learning. Across the country and around the world, Penn GSE’s more than 15,000 alumni are leading the way to increase opportunity for students of all ages. Their work builds hope and creates solutions to problems like insufficient funding, unidentified learning needs, poverty, and gaps in educational quality and availability. Here are just a few of their stories.

Fighting for Change in Public Education

To Helen Gym, C’93, GED’96, if the quality of American public education is at stake, so are the values at the heart of our democracy. “The promise of public education in the United States has represented a unique approach to building a just and inclusive society,” says Gym. “Our public schools are meant to take all children, no matter what their background, and give them the tools and environment they need to grow into their fullest selves.”

In the face of Philadelphia’s chronic school budget woes, Gym has become perhaps the city’s fiercest advocate for traditional public schools and the role of communities in strengthening them. Described by Philadelphia Magazine as “relentless, whip-smart, meticulously prepared, and utterly fearless,” she is determined to take community support to the next level in her new role as a Philadelphia City Council member.

“We’re proud to have overcome a destructive narrative that writes off our schools as failures, and to have built instead a dynamic grassroots movement that fights for a greater vision for public education.”

“We’re proud to have overcome a destructive narrative that writes of our schools as failures, and to have built instead a dynamic grassroots movement that fights for a greater vision for public education,” says Gym, who was elected in November 2015. During the past decade, she has organized parents across the city to raise their voices through Parents United for Public Education, an activist group she cofounded.

Parents United has helped parents protest excessive class sizes, scarce school nurses and counselors, and other circumstances resulting from the lack of stable funding for Philadelphia schools. In December 2015, the state took action to fix curriculum problems in four schools in response to a lawsuit from the group regarding insufficient school resources across the city.

“Philadelphia is grappling with the fact that it is the poorest large city in America, and it is in a state that is the worst in the nation in terms of the funding inequity between the wealthiest and poorest districts,” says Gym, mother of three children in district schools. “We live with the consequences of that every day.”

She says her run for office was inspired by the closure of two dozen Philadelphia schools in 2013, a growing tide of community activism, and the value she places on municipal politics.

“I saw more organizing than ever happening in faith communities, around kitchen tables, in school yards, and in civic associations. It felt like we had built political power beyond ourselves, and it was time to take this movement to City Hall,” says Gym.

She credits Penn GSE with providing a breadth of knowledge that has served her well in multiple roles. Gym enrolled in GSE’s Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) program while teaching full-time at Philadelphia’s James R. Lowell Elementary School. “My time at Penn GSE was an incredible opportunity to understand education from multiple vantage points and explore the relationship between research and practice,” she says. “Throughout my work, it has helped me to think about education in a fuller way.” That work has included activism with Asian Americans United and founding roles with both the Philadelphia Public School Notebook and the Folk Arts–Cultural Treasures Charter School in Chinatown.

The first Asian American woman to serve on the City Council, Gym begins her four-year term with school funding at the top of her agenda, and a sense of hard-won hope. “Schools have the opportunity to be the greatest anti-poverty effort our society can undertake,” she says. “It’s time to rebuild faith in our public institutions and the role communities play in driving the public will to make big things happen.”

Discovering How to Teach Every Child

Invisible obstacles thwart education when students’ particular learning needs and disabilities are not fully recognized and understood. Drs. Lynn Fuchs, GED’73, and Doug Fuchs, GED’73, imagine a day when customized interventions can ensure that every child learns.

“Millions of kids are learning virtually nothing because the seriousness of their problems is grossly underestimated or unknown,” says Doug. “We’re knee-deep in trying to figure out which learner characteristics and which academic interventions seem to go hand in hand, moving in the direction of tailoring education to the individual student.”

International leaders in the study of learning disabilities and named to a list of fourteen revolutionary educators by Forbes magazine in 2009, the husband-and-wife research team have already changed how children with learning problems are taught throughout the country. Their advances in curriculum-based measurement have given teachers tools to track student progress and vary instructional approaches based on data. They played a leading role in developing RTI (Response to Intervention), a program that provides early screening for learning differences and intensive tutoring that can put some struggling students back on track for general classrooms. Their programs in PALS (Peer Assisted Learning Strategies) use peer tutoring to meet a range of learning needs in reading and math.

“These interventions and practices are offered in a low-cost way to schools, and there’s documentation that their implementation produces better learning outcomes for children,” says Lynn, who holds the Dunn Family Chair in Psycho-educational Assessment at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College in Nashville, Tennessee.

Despite the success of the pair’s methods, a large category of students nationwide remains unresponsive to intervention. The couple’s current line of research aims to help these students. “I think you could rightly describe what we’re doing now as ‘personalizing’ education, in the way that some medical practitioners and researchers talk about personalizing medicine,” notes Doug, who holds the Nicholas Hobbs Chair in Special Education and Human Development at Peabody.

“I think you could rightly describe what we’re doing now as ‘personalizing’ education, in the way that some medical practitioners and researchers talk about personalizing medicine.”

The work is difficult, and it takes the researchers into sometimes uncharted territory. “For students with severe learning deficits, interventions have to be developed in very careful ways to compensate for a large variety of cognitive and linguistic limitations,” says Lynn.

She and Doug began their formal study of education at Penn GSE after discovering a shared commitment to helping at-risk children. Seeking to gain classroom experience, both earned master’s degrees and teaching certifications at GSE, where today they are consultants to The Center on Standards, Alignment, Instruction, and Learning (C-SAIL), directed by GSE professor and former dean Andy Porter.

“It was an intellectually stimulating year, and we enjoyed it very much,” says Doug of their student days. The two learned from revered GSE professors, studying teaching with Jim Larkin, measurement with Andrew Bagley, and literacy with Morton Botel, ED’46, GED’48, GR’53. After graduating, Lynn taught at Stonehurst Hills Elementary School just outside Philadelphia in Upper Darby, and Doug taught at Wayne Elementary School in Radnor Township, Pennsylvania.

Throughout their research over the past three decades, the two have kept the realities of schools top of mind. They test their interventions in the Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools, their primary research site, and strive to provide clear and practical instructions for teachers.

“School people juggle a lot of things, and the more complex the program, the harder it is to implement properly,” says Lynn. Adds Doug, “I think there’s an art and a science to creating programs that are effective and, at the same time, efficient enough to be used.”

Empowering Urban College Students

When Michael Sorrell, GRD’15, became president of Paul Quinn College in Dallas, Texas, enrollment was dwindling, the campus was in disrepair, and the school was deeply in debt. In 2009, it was in danger of losing its accreditation. Today, the college is lauded for groundbreaking programs that are opening up lifelong opportunities for students.

at a city law firm, he found again and again that the new friends he made were graduates of Paul Quinn, a historically Black college founded in 1872. Sorrell sought opportunities to support the college as a way of thanking his friends, and when the job of president opened up he applied at the age of thirty-five, with no experience in higher education.

“Predictably, I was not exactly greeted with an enthusiastic response,” he says with a laugh. “But my thought was, ‘you need a person who understands business, who understands relationships.’” Offered a spot on the board instead, Sorrell accepted the post and watched the college go through four presidents in five years until he was offered the top post at a time when, he says, no one wanted the position.

President since 2007, Sorrell has launched a series of dramatic initiatives to make Paul Quinn both effective and empowering for students from a variety of racial and socioeconomic backgrounds, but especially those experiencing poverty.

By adopting a “work college” model that assigns students jobs on and off campus, Sorrell has decreased tuition. “Students from Pell Grant backgrounds can graduate with less than ten thousand dollars of debt, and they get two forms of education—a real-world work experience, and a rigorous liberal arts experience,” he says. Classroom learning is tailored to have relevance to students’ lives. “We believe that we can teach you anything by incorporating your life and background into the lesson plan,” says Sorrell. “We can teach you poetry by analyzing Rudyard Kipling’s ‘If’ and discussing it in the context of your childhood in an inner city.”

“We believe that we can teach you anything by incorporating your life and background” into the lesson plan.”

Sorrell worked to change students’ perceptions of their role in the community, turning the college’s abandoned football field into a student-operated organic farm. The farm donates and sells fresh produce locally, offering a needed product in an area considered a “food desert.” Sorrell explains, “The act of giving empowers you and begins to transform your narrative.”

Fully accredited and with an enrollment that has nearly doubled in five years, Paul Quinn has received the 2011 Historically Black College or University (HBCU) of the Year Award, the 2012 HBCU Student Government Association of the Year Award, and the 2013 HBCU Business Program of the Year Award from HBCU Digest. Sorrell was named to the 2013 President’s Higher Education Community Service Honor Roll.

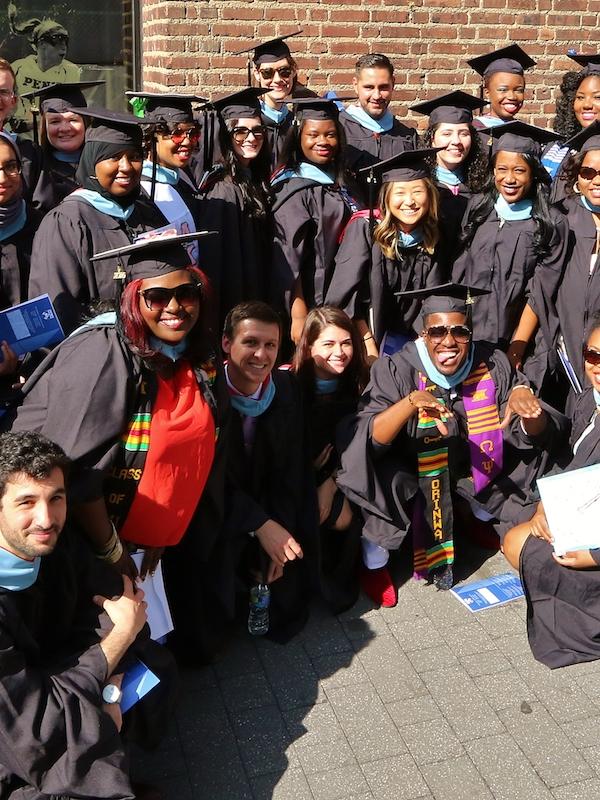

A graduate of Penn GSE’s Executive Doctorate in Higher Education Management program, Sorrell undertook his doctorate while leading Paul Quinn. “The total experience was fantastic, and for all the degrees I’ve been fortunate enough to attain, I have a closer bond with my classmates from Penn GSE as a whole than I do from anywhere else,” says Sorrell, who studied work colleges for his dissertation. “They’re a set of people I can call and brainstorm with, who I know have my best interest at heart.”

Sorrell has the highest standards for Paul Quinn and its students. “My expectation is that our students will go out and change the world,” he says. Looking ahead, he makes it clear the school’s ascent is far from finished. “We’re trying to reinvent urban higher education,” he says. “To be frank with you, I haven’t even taken the best stuff off the shelf yet.”

Fostering Critical Thinking in the Classroom

When Andrew Biros, C’10, GED’12, undertook his student-teaching assignment in Penn GSE’s Teacher Education Program, he found that too many of his pupils at University City High School in Philadelphia did not expect to be active participants in the classroom.

At Penn GSE, Biros learned to teach using the inquiry method. A student-centered approach, it encourages students to play a leading role in learning. “The teacher is a facilitator, a coach, a curator of curriculum who helps students ask the right questions and find the right resources to answer them,” says Biros, who attended GSE with a Leonore Annenberg Teaching Fellowship, considered the equivalent of a national Rhodes Scholarship in teaching. An inquiry methods teacher also strives to make the classroom relevant to the lives and backgrounds of the students.

Biros has championed this technique in two Philadelphia public schools and is now making it the focus of his work launching charter schools in California. At University City, Biros mobilized his high school seniors to better understand problematic issues in their community. He asked them to generate questions and analyze data about low educational attainment, poverty, and crime, and arranged for then-Philadelphia mayor Michael Nutter, W’79, to visit his class and respond to students’ questions about how citizens and government can effect change.

“We can begin to instill students with the notion that, ‘Yes, I can solve this.’ When people are empowered with that, what we can accomplish as a society will be endless.”

After graduating from Penn GSE, Biros worked for three years as a full-time teacher at the Kensington High School for Creative and Performing Arts, another public school in Philadelphia. There, he led efforts to redesign the school’s curriculum according to the inquiry method, working with colleagues including two former GSE classmates, Monty Ogden, GED’12, and Charlie McGeehan, GED’12. Their approach also emphasized technology, assigning every student a Chromebook laptop. “Students need the right tools so that they can be engaged learners and exhibit new understandings,” Biros says.

Since last summer, Biros has been developing charter schools in California with the support of the Silicon Schools Fund, a venture philanthropy foundation. To help launch a school in the established Alpha Public Schools network, which serves low-income communities, he has taken on responsibilities in management and operations in addition to teaching and curriculum development. In 2018, with support from Silicon, Biros plans to open his own school, the Collaborative Design Academy, slated to serve a diverse student population beginning with grades four and five and expanding through grade eight. Having worked in public and charter schools, Biros says he sees both as viable vehicles of educational progress. “What I care about is fostering unique and innovative school models,” he says. “I just want great schools, whether charter or public.”

Biros credits GSE with shaping his work through both the inquiry method and close-knit relationships with his classmates. “It was probably the most vibrant year of my academic life,” he says. “To be able to teach in a school and then attend class with my cohort at GSE and reflect on our work was really special. When teachers go into their classrooms and close the door, it is incredibly isolating. But when they are able to reflect and collaborate together, it is incredibly powerful. That’s where real growth comes from.”

Reaching Children Around the World

Shruti Bhat, GED’15, wants to bring education to children in marginalized places and communities around the globe. In the mountains of Tajikistan and the urban slums of Bangladesh, she has applied the training of Penn GSE’s International Educational Development Program (IEDP) to make learning better for vulnerable young people.

After earning her bachelor’s degree in accounting and marketing, Bhat worked for accounting firm KPMG. During a vacation, she volunteered with a nongovernmental organization in Costa Rica and learned about career paths supporting change in developing countries. From there, she decided to take such a path, seeking classroom experience by teaching English in Peru while applying to master’s programs.

“Penn GSE was my first choice,” says Bhat. “I was drawn to the IEDP professors, classes, and internship program. I was so excited when I got my acceptance letter.”

An IEDP course taught by Dr. Ameena Ghaffar-Kucher, GSE senior lecturer and IEDP associate director, set Bhat in the direction of her current work. Bhat and a group of her classmates worked remotely with the Aga Khan Foundation in Tajikistan to design a curriculum for children in a minority population known as the Pamiri. Bhat asked to continue this work when it came time for her to fulfill the IEDP’s international internship requirement, and Ghaffar-Kucher helped her arrange to work onsite with the foundation in a mountainous region of Tajikistan bordering Afghanistan.

“Tajikistan is one of the poorest post-Soviet countries, and the area where the Pamiri live is poorer than the rest of the country,” says Bhat. “I visited schools and talked with teachers to hear firsthand what their challenges were. The IEDP prepared me to listen and get input from community members, because they are the experts on what they need.”

Bhat’s efforts resulted in an early childhood curriculum for teaching the national language of Tajik to Pamiri children, who are raised speaking a local dialect. Today the curriculum is being reviewed for approval by the government of Tajikistan, and Bhat has relocated to Bangladesh, where she works as an early childhood development consultant at the Aga Khan Foundation. Her role builds on her internship experience, focusing on curriculum development for forty early-childhood centers in urban slums throughout the capital city of Dhaka. The children, whose parents work primarily in garment factories, range in age from two to six.

“We want to ensure healthy conditions, and proper care and education for them,” says Bhat. When she is not developing learning resources for the centers, Bhat utilizes her accounting and marketing background to build an operational and financial sustainability plan for the centers with her colleagues at the foundation.

“I feel that if we educate children and provide a more tolerant outlook for them, they can have the ability to change the future of their communities through their mindsets and actions.”

In the long term, she has big plans for the power of education in the world. Of Indian origin and deeply troubled by the conflict in Kashmir between India and Pakistan, Bhat often thinks about the role education could play in creating peace across national borders. “This may be very idealistic, but I feel that if we educate children and provide a more tolerant outlook for them, they can have the ability to change the future of their communities through their mindsets and actions,” she says. “Combined with health and other social services, I think education is one of the most powerful tools for change.”This article originally appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of The Penn GSE Magazine.